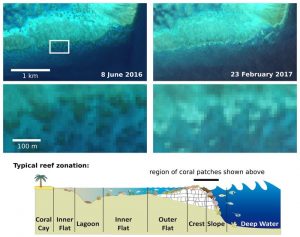

Images from the ESA Copernicus Sentinel-2A satellite captured in June 2016 and February 2017 show coral turning bright white for Adelaide Reef, Central Great Barrier Reef. (Credit: Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2016–17), processed by J. Hedley; conceptual model by C. Roelfsema)

Studying European Space Agency (ESA) Sentinel-2 images captured over the reef between January and April 2017, scientists working under ESA’s Sen2Coral project noticed areas that were likely to be coral appearing to turn bright white, then darken as time went on. The event was confirmed by two successive images captured in February, indicating the approximate duration of the bleaching being at least 10 days.

The corals of the Great Barrier Reef have now suffered two bleaching events in successive years, and experts are concerned about the capacity for reef survival under the increased frequency of these global warming-induced events.

Bleaching happens when algae living in the corals’ tissues, which capture the sun’s energy and are essential to coral survival, are expelled owing to high water temperatures. The whitening coral may die, with subsequent effects on the reef ecosystem, and thus fisheries, regional tourism and coastal protection.

The bleached state of a coral can last up to six weeks. The corals might recover, or die and become covered by algae, in either case turning dark again, making them difficult to distinguish from healthy coral in a satellite image. Such a pattern requires systematic and frequent monitoring to reliably identify a coral bleaching event from space.

“In general, interpreting changes is ambiguous,” noted Dr. John Hedley, scientific leader of Sen2Coral. “You can’t just jump to the conclusion brightening is bleaching, because the brightness of any spot on a reef varies from image to image for many reasons due to water and bottom changes.”

To confirm the imagery, Chris Roelfsema of the University of Queensland’s Remote Sensing Research Centre, and lead of the Great Barrier Reef Habitat Mapping Project, conducted field campaigns in the area, collecting thousands of geo-located photos of the corals in January and again in April.

“Sadly, in the areas where bleaching can be seen, the abundant coral cover we observed in January was in April mostly overgrown with turf algae, with only some individual coral species surviving,” he said. “The imagery and field data suggest this area has been hit badly.”