Currently, about a dozen government and commercial Earth-imaging satellites circle the Earth daily. They take thousands of pictures that governments, private companies, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) use for purposes as varied as monitoring wheat production, looking for point sources of pollution, and displaying images on Google Earth.

Long before the launch of the first Earth-imaging satellites, some envisioned using them to help prevent wars and atrocities by detecting, proving, and publicizing acts of military aggression and large-scale violations of human rights. Now that these imaging capabilities are well established and the quantity and quality of the available satellite imagery is steadily increasing, we are better able to understand its benefits and limitations for these purposes.

Satellites cover vast swaths of the Earth’s surface every day, but not all of it. Additionally, searching the huge amounts of imagery that they collect for evidence of preparations for attacks is an overwhelming task even for large intelligence agencies, let alone for NGOs. Therefore, a critical component of any Earth observation mission is tasking the satellites—that is, instructing them to maintain or vary their orbit and where to point their cameras along their path. This requires some knowledge of where to look.

The United Nations’ satellite imaging agency, UNITAR/UNOSAT (short for United Nations Institute for Training and Research Operational Satellite Applications Program) maintains a hotline staffed around the clock by duty officers. Launched thirteen years ago to make the benefits of satellite remote sensing and GIS available to its sister UN agencies, UN member states, and their citizens, UNITAR/UNOSAT works exclusively in response to requests, usually from UN agencies.

“We have been working on internal conflicts where there’s a humanitarian aspect,” says Einar Bjorgo, the agency’s manager, who points out that it has not yet worked on detecting military build-ups and preparations for trans-border attacks. “Typically, we first get a request from a humanitarian actor to understand what the internal situation is like, because in these situations there is little or no access to objective field information for security reasons. So that is exactly where satellite imagery can come in and play a very important role: to be the eyes of the UN and the international community as to what goes on during conflicts. Often, either during or after the event, we are requested to do specific assessments related to potential human rights violations. We provide our objective, neutral, image-based scientific analysis. That is then compared against interviews and media reports and volunteer information, etc.”

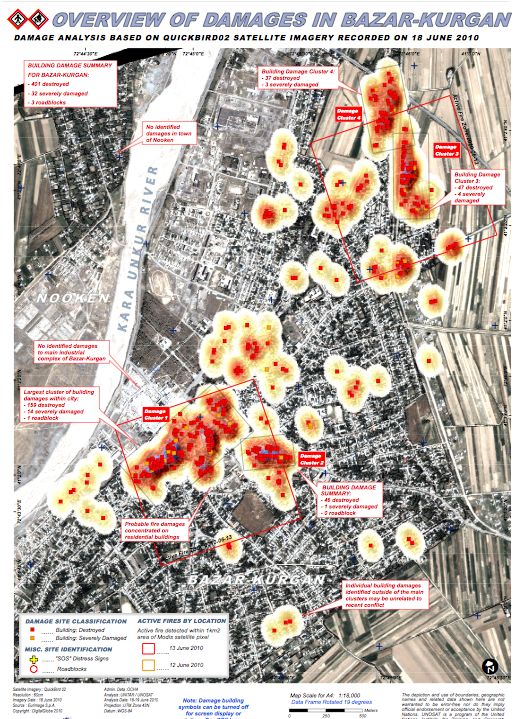

During the Kyrgyzstan conflict, a couple of years ago, UNITAR/UNOSAT received reports of ethnic violence, Bjorgo recalls. “We used very coarse satellite imagery to see whether there was fire detection, because there were reports of houses being burned. Indeed, we did see fire signals in an urban environment. Then we were able to program much more detailed commercial satellite images and do damage assessment and ongoing monitoring of this situation.” The MODIS satellite fire detection system, he points out, can potentially be used for early warning for such conflicts because it can detect fires starting in areas where they do not typically occur due to the season or the place.

Bazar-Kurgan Damage Assessment by UNITAR/UNOSAT from 22 June 2010. Imagery from DigitalGlobe

Bazar-Kurgan Damage Assessment by UNITAR/UNOSAT from 22 June 2010. Imagery from DigitalGlobe

While it is difficult to use satellite imagery to detect the movements and actions of small units, at times attacks can be predicted by imagery showing encampments or amassed equipment, such as trucks. Often, however, this can only be done after the fact. For example, if unclassified information about atrocities indicates a pattern of attackers burning down villages, imagery can be used to detect burnt villages that were intact in previous imagery. “In cases like Sudan, it’s a little bit of chicken-or-egg,” says Jim Stokes, Vice President of Commercial Insight Solutions at DigitalGlobe, where he leads a team of imagery, geospatial, and oceanographic experts that deliver information on a subscription basis. “Prior bad events help us understand future bad events.”

“Some of our ongoing customers give us information they have to help drive our collections,” says Andy Dinville, DigitalGlobe’s Senior Manager for Analytics. “For instance, we’ve worked with the Satellite Sentinel Project in Sudan to try to understand from their sources some of the things that are going on to help point the camera on the satellite at some of the places where there are express concerns of human rights violations occurring or attacks or harassment activities going on.” DigitalGlobe also monitors events around the world, such as typhoons, and tries to anticipate where they will have the greatest impact, so as to maximize its chances of collecting valuable imagery. “After the event happens, there’s something you can see in the image, but if you’re monitoring the situation throughout the event, then you can chronicle what’s going on,” says Dinville.

Evidence of airstrike outside of Jau, Unity State, South Sudan. Credit: DigitalGlobe

Evidence of airstrike outside of Jau, Unity State, South Sudan. Credit: DigitalGlobe

Often, knowing where to point the cameras on commercial satellites depends on tips from governments, according to Tim Brown, Senior Fellow at GlobalSecurity.org, an independent research organization. “Say that Syria intervened in Jordan or Turkey or across the Golan Heights into Israel. Using unclassified satellites to detect that sort of activity, publicize it, and deter it, really depends more on cross-cueing from the extensive resources of the U.S. and allied intelligence community. Preparations for missile attacks from Syria into Israel or preparations for a build-up along the Golan Heights for an invasion into Israel from Syria is not something that the commercial satellite system is really able to handle on its own. We are not going to discover it because some international NGO detects a build-up. Rather, there are going to be leaks from U.S. intelligence and administration officials to the New York Times or the Washington Post, saying that we detected evidence of a Syrian build-up and then, once that gets out, human rights organizations and commercial satellite providers are going to start focusing their resources on trying to determine whether it is actually happening and, if it is, to document it.”

Acquiring the right imagery from the right place at the right time is only the first step. Next, it has to be analyzed and used to make maps. UNITAR/UNOSAT conducts its own satellite image analysis, mapping, and reporting. Additionally, as part of UNITAR, it trains people who work in national ministries, UN agencies, and NGOs on the use of the technology for disaster risk reduction (DRR) and for humanitarian response. “Very often there’s too much focus on access to the actual images and the raw data, while what a lot of people need most of the time is the derived information, such as the extent of a flood,” Bjorgo says. “So our mission is to build capacity and to deliver this expertise.”

Over the past couple of years, the relatively few commercial satellite image vendors have increasingly begun to also provide services. However, what sets UNITAR/UNOSAT apart from them, according to Bjorgo, is that since its inception the agency has been working with a full range of commercial, scientific, and governmental satellite sensors, so it has a very wide technical expertise. “Also, because we’re not commercial, and because we’re a UN program, we are in very close contact with the user community in the field, we really understand their need. Not working for profit at all allows us to develop together with them more sustainable solutions, in an environment of trust through objective solutions.”

Depending on cloud coverage and other conditions, from the moment it receives a request UNITAR/UNOSAT can take from one to three days or longer to produce an image. “Once we have the image in-house, if it’s really urgent we typically print out the first product within six hours. That’s just a quick overview. Then we can make our refined, more detailed product the next day. Normally, if we can get an image within 24 hours of the request we’re really quite happy. For crisis situations, the important thing is to make the images available very, very fast to us and in formats that are easy to use—not what we saw ten years ago, when the formats were highly proprietary and you received the images on a CD in the mail a few weeks after the event was over.”

Bjorgo acknowledges that remote sensing “cannot do everything” and this is where the combination of field assessment and remote analysis comes in. “We play our part and our field colleagues play their part and together we now have a much better system in place than before.”

Analysts can extract features from satellite imagery to identify the source of certain attacks. For example, Stokes explains, if there were reports that a group was turning vehicles into IEDs by cutting out the back seats and making other modifications, a key component of an effective counterstrategy would be to use satellite imagery to look for garages, car junk yards, or scrap metal yards.

Currently, the biggest challenge in using satellite imagery to detect and monitor military activities and human rights violations is efficiently managing and exploiting the vast amount of data that is being collected. “We’re trying to help fuse the data sources that exist, and specifically, of course, some of the things that we at DigitalGlobe can do to add perspective to some of the data that we assemble,” says Dinville. “On a daily basis, there is an ever-growing mountain of data out there. There are webcams, there are social media sources, there are ever-growing media feeds, and almost anyone can publish data and make it readily available to a broad community.”

DigitalGlobe collects satellite imagery from around the planet at least at half-meter resolution and geo-references it using standard geo-spatial datasets, such as roads and administrative boundaries. The imagery’s resolution is sufficient to show individuals and the size of crowds, whether in Tahrir Square or on the Washington Mall. By fusing data from social media with satellite imagery, “you can take a snapshot in time of those locations,” says Dinville. “We are working with all of those types of data to try to provide more awareness and what we hope to be a more objective assessment of what’s happening on the ground.”

“With the volume of satellite imagery that we’re able to collect on a daily basis, our challenge is to process that daily load, turn it around, and make it available rapidly,” says Dinville. “We use crowd-sourcing to get it in the hands of the right people, to observe, to evaluate and to monitor some of these events that provide derived information.” This crowd-sourcing includes both experts and non-experts, he explains. “If I’m looking at military equipment, I certainly need a military analyst to try to help support that. But if I’m looking for a lost ship off the coast of Australia, frankly, I need any set of eyes that have had any experience looking for something that doesn’t look like open water.”

This image shows Cairo’s Tahrir Square on February 11, the day Hosni Mubarak gave up the Egyptian presidency. An estimated 300,000 protesters gathered into downtown Cairo. Credit: DigitalGlobe

Enormous advances in recent years in the ability of computers to quickly analyze large data files from satellites have greatly increased the ability of analysts to rapidly assess change, Stokes points out. “Change is really the key to all this. Something’s there yesterday and it’s not there today, or something that wasn’t there yesterday is there today, associated with these global atrocities. We’re much better able to detect that in a much shorter window of time.” Furthermore, the huge advances in data production, data download, cloud analytics, and image archives, he argues, have greatly improved the ability to understand that change. “Fifteen years ago, you really couldn’t do that and today I can, within minutes, look at ten different images from ten years and tell you what’s changed.”

[Correction] DigitalGlobe has a growing analytical capability that was part of the legacy GeoEye organization, and they continue to invest in that business. DigitalGlobe Analytics combines Earth imagery, deep analytic expertise, and innovative technology to deliver integrated intelligence solutions. Analysts currently support security missions embedded with combatant commands, special operations and other USG mission partners as well as supporting a growing list of NGO’s like the Enough Project and the Satellite Sentinel Project. DigitalGlobe had its own imagery analysis center that was helping NGOs develop document sources and its business model was to get other countries, NGOs, and the United Nations to purchase their value-added analysis products, says Brown. However, he says, the company decided that is was not a viable business model and “pulled the plug on it.” NGOs can still buy the imagery to document abuses, but now have to analyze it themselves.

The resolution of half a meter or better of unclassified commercial imagery is sufficient to recognize the presence of people on the ground—for example, refugees, protesters, or military personnel—as well as to type vehicles. “For instance, across Africa, we can recognize UN vehicles bringing relief supplies to an internally displaced persons (IDP) camp,” says Dinville. “The combined analytic capability of unclassified satellite imagery at its current resolution and information available through unclassified means is more than adequate to expose left-of-boom activities,” says Stokes, using a military term for the precursors to an attack.

This image of Brasilia, Brazil, on 15 June 2013, taken by WorldView-2, captures a crowd protesting the Brazilian government’s decision to raise bus fares. Courtesy: DigitalGlobe

This image of Brasilia, Brazil, on 15 June 2013, taken by WorldView-2, captures a crowd protesting the Brazilian government’s decision to raise bus fares. Courtesy: DigitalGlobe

However, Brown points out, NGOs will never be able to equate what the U.S. government can see and know. “The total U.S. intelligence budget is something like $75 billion; three quarters of that is contracts to do such things as buy satellites, build server farms, and build intercept capabilities. I don’t see the NGO community as being able to ever do anything close to that.”

UNITAR/UNOSAT uses the full range of unclassified imagery, from both government satellite agencies and commercial providers. This can be a challenge, says Bjorgo, because of the number of data formats and new developments. From commercial satellite companies, it acquires mostly very high resolution imagery. Increasingly, UNITAR/UNOSAT buys imagery, due both to its improved finances and to the fact that the commercial companies have dropped their prices.

The imagery available for free on Google Earth is “stale,” Brown says. “It gets updated more frequently in some areas, but if you want to see yesterday’s photo of where the Syrians were shelling a town outside of Damascus, you have to pay money for it.”

Military and paramilitary forces may learn to adapt to the new era of satellite remote sensing, by hiding or disguising their activities. “I haven’t observed it,” says Stokes, while acknowledging that it is “certainly feasible.”

“We can’t fly the satellites in a different pattern very easily,” Dinville points out. “They fly across at 10:30 in the morning local time. So you can cover things up, put things in a shed, or not do things at that time of day and avoid being seen by our satellites. But some things cannot be concealed. If somebody’s moving military equipment from one place to another, if I can observe their presence one day, and they’re no longer there another day, I may not know where they’ve gone, but I know that they’re no longer there. And if I continue to watch an area like that, they’re going to have to show up somewhere. This is why we think it’s important to try to observe events over time. DigitalGlobe’s five-bird constellation allows us daily revisits, sometimes multiple revisits on a given day, that give us the ability to watch some of these areas of interest.”

Bjorgo would not rule out the use of camouflage or other techniques to hide from or deceive imaging satellites. “One can assume that, with time, some of these actors may take increased measures in order to make it more difficult to be observed from satellites. In that sense, maybe our job will be more difficult in the future. However, for large-scale violations there are limits as to how much you can hide.”

The Syrian military knows when the satellites fly overhead, Brown says, so they can decide to kill people only at other times or wait for bad weather. “There are ways of getting around satellites.”

The ability of UNITAR/UNOSAT and of NGOs such as the Satellite Sentinel Project and Human Rights Watch to monitor ongoing atrocities and regional problems around the world is unprecedented. “It is extremely different from what it was during the breakup of Yugoslavia and the Russian intervention in Chechnya,” says Brown. “Satellites now provide a much greater ability to monitor and document what is going on.”

Ultimately, however, do governments and rebels behave differently because they are aware of being “watched” by satellites? It may be too soon to tell. When Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, leading to the first Gulf War, there were not enough commercial satellites to capture the event and the current constellations of Earth observation satellites still barely existed when the United States invaded Iraq in 2003. “Satellites have not yet been used to document a cross-border intervention,” Brown points out.

While Bjorgo can point to humanitarian disasters in which governments used satellite imagery to make important decisions—such as planning food assistance in Pakistan or relocating refugees out of shelters built in areas prone to flash floods in Haiti after the earthquake—he cannot cite any examples of governments changing their military behavior due to it. “One can speculate,” he says, “but it would be just that. I don’t have any statements or anything to show that state actors or non-state actors directly change their behavior as a result of our activities related to conflict situations. It is of course an interesting research question.”

According to Dinville, however, DigitalGlobe’s work in Sudan and, more recently, in Egypt provides some examples of behavioral changes brought about by satellites. “Both Sudan and South Sudan are being watched,” he says. “The satellite imagery that we’ve used has at least helped illustrate and illuminate actions by both parties to help make them understand that they can’t just do whatever they want and have no consequence. As we collected imagery over Tahrir Square, we saw more people joining the protests and the military backing off a little bit because they knew that they were being watched. The more we can monitor these events and get the information out rapidly, collaborating with reliable information sources to document these events, the more it will have an impact.”

Brown is skeptical. The real question, he says, is leveraging all that data and turning it into deterrence for actors who are violating international norms and as evidence to prosecute war crimes and crimes against humanity. The effort to document what the Syrian government has done is unprecedented, he points out, yet despite images of carnage, destruction, and mass graves from both satellites and sources on the ground, the Syrian government remains committed to maintaining control.

“In spite of all this technology and all of this effort, it has not deterred or dissuaded Assad. I think it is admirable, but I don’t know whether it is actually going to work. I haven’t yet seen a case in which satellite imagery has deterred a regime from using a military capability or compelled a regime to stop using one.” Ultimately, he believes, “a ground photo taken with an iPhone of a mass grave or of burnt corpses in a village is much more capable of moving public opinion than a photo from even the most advanced spy satellite.”

UNITAR/UNOSAT recently signed an agreement with the International Criminal Court that enables the latter to rely on UNITAR/UNOSAT expert analysis for the cases that are brought to it. Bjorgo expects this collaboration to become “almost routine for any upcoming war-crime cases, as long as imagery can bring something to the table.”