In the last 20 years many western ideas have been adopted in Poland, among them the idea of sustainability. However, the idea is often misunderstood, because the English word “sustainable development” is difficult to translate into Polish; the most common translation actually means „balanced development”. In spite of that, „sustainable development” (balanced development?) has become a very popular slogan among local politicians and urban planners, and it is very difficult to find a planning document which is not justified by this “principle”.

However, some politicians or even planners believe that sustainability means single-family housing in the suburbs and urban highways. Actually, sometimes one gets an impression, that almost everything can be labeled sustainable.

In our paper we ask: how sustainable polish cities really are? We are skeptical to some political declarations which pretend that “black is white”.

We believe that “sustainable city” is not only a slogan, but a city which is characterized by compact urban structure and high-density zoning, affordable housing, large share of public and bicycle transit, and attractive public space (see for example Leipzig Charter on Sustainable European Cities or the U.S. SustainLane ranking).

We use this framework to compare the visions and reality of urban development in Poland. Our case study is the city of Poznań, one of the largest Polish cities with over half a million inhabitants.

In short, Poznań is a city of universities, but also a strong regional economic center, located in the middle between Berlin and Warsaw.

Unfortunately, the city has lost many inhabitants because of suburbanization. In the political declarations and development plans one can read much about avoiding urban sprawl, maintaining compact urban structure and attracting more people to live in the city. And what about the real policy?

It is quite the opposite: decline of the inner city, zoning for thousands of single family houses at the outskirts and plans for an urban highway (ring road).

Housing

A sustainable city should offer affordable housing, otherwise those who cannot afford a flat will move to other cities or to the suburbs. The “housing question” in Polish cities has a long story.

Under socialism, the state-controlled and inefficient housing market could not cover the demand, which increased rapidly due to industrialisation and inflow of workers from the rural areas. The state did not invest in the old pre-war housing stock, but built new prefabricated housing estates instead. Housing shortage poses a serious problem even many years after the fall of socialism.

In the largest Polish cities, such as Poznań, it is very difficult to find a dwelling at a good price. Because of its growing economy (GDP 2x higher than national average, unemployment rate under 5%) and the high share of young people (over 100,000 students, many of whom stay in the city having finished the studies), Poznań has got exceptionally large demand for housing.

Unfortunately, it is very difficult to find affordable housing in the city because of housing shortage and high prices. In the communist times and in the 1990s the supply of housing was short, but the dwellings were not expensive.

Today most new dwellings are supplied by private developers (53% in the years 1995-2008, but 77% in 2009!), soonly the more affluent people can afford them. Housing prices doubled during the so-called “housing boom” (2006-2008).

The average price per m2 is about 7,000 złoty at the primary market, and about 6,000 zloty at the secondary market (1 EUR = ca. 4 złoty). For the average salary, it is only possible to buy about 0.5 m2 of a new flat – that is much less than in most Western European cities. There is no choice for the low- and middle-income households, because the share of social housing is decreasing (25% between 1995-2008 and only 7% in 2009).

The extremely high housing prices in Poznań, especially in the inner city, force many households to move to the suburbs. However, urban sprawl is also a result of urban planning. In the 2008 development plan many agricultural areas at the urban fringe were zoned for low-density single family housing. It is a new direction in the planning policy, because previously the vast majority of new housing was apartment houses.

However, it is doubtful whether the city will be able to supply the necessary infrastructure (roads, transit, schools, kindergartens etc.) to the new low-density districts. Especially that in the last years the city spent much money on various events (for example, 700 million złoty, i.e. about 175 million EUR for the reconstruction of football stadium for EURO 2012), and the ratio of municipal debt is very high.

Urban Renewal

Poznań city center was historically formed into a nearly perfect 1 km radius circle area within the former Prussian fortress (pulled down nearly 100 years ago). It consist of the medieval Old Town (Polish) and the so called XIXth century ‘new’ city (Prussian).

There were almost 70,000 inhabitants within this area in 1885. Nowadays, the city center itself has about 36,000 inhabitants, but according to official prognosis delivered in 2004 by the University of Economics Regional Statistics Center, this number will decrease to nearly 30,000 till the year 2030.

The outflow of inhabitants has been clearly visible in the last years. For example, in the St Martin quarter (one of the main in the city center), there were nearly 13,500 inhabitants 10 years ago. Now, it counts only 7,000. One of the first serious warnings was expressed in 2007 in the URBACT report: “Support for Cities project. Assessment and options report for Poznań”.

The author (Karsten Gerkens, director of Office of Urban Regeneration and Residential Development, City of Leipzig, Germany) alarmed, that the city center, although accumulates significant historical, architectural and cultural potential, was not properly protected and maintained. The vast areas of historical buildings, even along main streets, remain in critical technical and aesthetical condition.

In fact, during the communist period old buildings were treated as an attribute of the old, capitalistic system, thus almost totally neglected (some of the historical frontages were in fact completely demolished and replaced by modern blocks and ‘skyscrapers’).

But even during the last 20 years of the new capitalistic system, the municipal policy has not improved significantly (in Poland land use planning is still associated with central communist planning system).

The most exposed civic buildings have been renovated thanks to European funds, but the rest of the urban tissue is not taken into consideration within any strategic plan. Gerkens indicated a special role of the post-industrial facilities, especially the Old Gas-Works and the Old Slaughterhouse areas, which are 100 years old complexes of industrial brick buildings.

Their urban and cultural potential could be compared to the Old Brewery complex, which is a successful example of revitalization, and became the most famous Poznań shopping center, localized within the city core.

The center of Poznań has always offered a wide choice of shops, for example bookstores. Unfortunately, in the last years it has lost many shops which cannot afford a high rent.

Although the city itself owns some rental space along the main streets, it has not introduced any incentives to keep the less commercial activities in the city center.

This caused a gradual, yet inevitable loss of pedestrian interest and presence within the public space. Short after the huge extension of “The Old Brewery” in 2007 and “Galeria Malta” in 2009 (shopping mall just on the fringe of the city center), the commercial rents along the St Martin Street were (inadequately to the demand) doubled or even tripled by house owners.

This forced many vendors to move to the shopping malls, or to close down the shops (including several bookstores).

Thus, existing public space is gradually transforming into a one, unified banking center. At the moment, it is mainly the financial sector only, that can cope with rent increase and take over empty private and municipal commercial spaces.

Transport Policy

The answer for the rising number of cars in Poznań (in 2009 there were more than 500 cars per 1000 inhabitants) is the construction of new roads to the suburbs, as well as ring roads. This way of thinking has been presented by the city of Poznań and surrounding municipalities. Main transport investments in Poznań in the last years were roads connecting city with growing suburbs.

However, this policy does not solve the problems – traffic jams have just been moved from the city limits to districts located closer to city centre. The city council plans also the construction of urban highway as a third bypass of the city.

It should be located with a radius of 5-7 km from the city centre. The cost of the 36 km long highway is estimated at about 2 – 2,5 billion EUR. Some construction works were started in 2009 although the financial feasibility of project is impossible to reach.

Simultaneously to these big investments the city has made numerous improvements for automobile traffic, such as: broadening the roadways, creating park places, giving cars priorities on intelligent traffic lights etc.

Consequent development of public transport system would be much cheaper than the expensive construction of urban highway. Unfortunately, the local public transit policy aims only to optimize the tram network in the city centre (e.g. to eliminate “bottle necks” and reduce unnecessary lines), rather than to extend the network to new settlements or to the campus of Adam Mickiewicz University, which is also located in the suburbs.

The last extension of tram network was the “Poznań Fast Tram” opened in 1997, after 16 years of construction works. Consequently, the number of passengers has been declining, and the motorisation rate has been growing.

Neither public transit, nor bicycles are perceived as an alternative to automobile. The modal share of bicycle traffic is very low – about 3%. The main barrier is: lack of facilities (bicycle ways, stands) and their low quality, which is far from cyclists expectations.

Urban Sprawl

Owning suburban home with a garden and a large garage has become a dream of many young people in the last few years. This image similar to “American suburban way of life” has been created mainly by media and pop culture, but it is also a reaction against grey and boring large housing estates from socialist times, and decaying old districts.

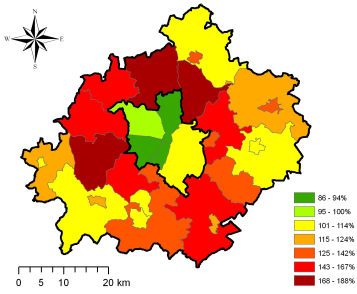

People are motivated to move to the suburbs first of all by lower prices of flats, better quality of environment and, especially, silence. Poznań metropolitan area has been witnessing a self-sustaining suburbanization process for at least two decades.

The population of the central city has decreased: in 1990 Poznań had had 590 000 inhabitants, two decades later almost 554 000, but the population of the entire metropolitan area has grown. Negative migration balance of the central city is accompanied by positive migration balance of suburban communes.

Furthermore, strong residential mobility is also observed within the city limits: from the central districts to the peripheral ones, from blocks of flats and tenement houses to detached houses as well as to modern condominiums.

The suburbs of Poznań are witnessing the features of urban sprawl. Many new estates do not have a connection to existing urban structure and public transport, especially rail. The choice of location is usually chaotic, resulting from a “play” between landowners (farmers), developers and office responsible for agriculture land protection, rather than spatial development plans.

Urban chaos is strengthened by growing number of new single-function facilities, e.g. shopping malls, industrial zones, technology parks as well. They are also located far away from existing bus lines and rail network so private cars are the only means of transport assuring efficient and rapid transfer between these spread sheds and compounds.

Summary

A few years ago hardly anybody heard about “sustainable cities” in Poland. Today, it has become a very popular slogan among urban planners and politicians. But slogans are good enough for elections, not for planning. There is an obvious incompatibility between political declarations and real decisions. It is just like trying to sell an old product under a new, more attractive label. Why do people buy that? Maybe because they do not have enough knowledge to choose the best option. Thus, they let the politicians themselves make the choice. For now, people seem to underestimate how important urban planning is. Or they simply think it is all about bureaucracy.

Of course, there are engaged citizens who want to take an active part in planning processes. These are small but well-organized groups, motivated by ecological or social reasons. Although usually they are not treated as partners by the local authorities, they managed to achieve some small successes (for example, a neighborhood park). But all in all, there is not enough planning awareness and the public participation in the planning processes is often treated as a facade. It is a great task for the (good-minded) planners to explain to the public the true costs of sprawling urban development, often defeated by short-sighted politics. Citizens should be aware that when they move to a single-family house in the suburbs, they will not only have to commute very long distances, but they also may not have a paved road. If there are more and more shopping malls around, the city center area will ultimately become a concrete desert. If we do not want it to happen tomorrow, we have to act today. This is the real sustainability. If not this, what else might be?

—————————————————————————————-

Dr Adam Radzimski, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań – Email: [email protected]

Dr Michał Beim, Kaiserslautern University of Technology – Email: [email protected]

Dr Bogusz Modrzewski, The European Career College, Poznań – Email: [email protected]