Part one of this series described an imagined future scenario of pizza deliveries made using unmanned aerial systems (UAS). This is hardly a stretch given Americans’ history of extraordinary innovation. The level of innovation with UAS technology promises to be breathtaking. Since Part 1 was published, I have found real life examples of similar UAS entrepreneurship. Beer was parachuted from UAVs to eager fans at a music festival in South Africa. The flying “hops helis” were dispatched to their locations via smartphone orders. Welcome to the revolution!

Part one of this series described an imagined future scenario of pizza deliveries made using unmanned aerial systems (UAS). This is hardly a stretch given Americans’ history of extraordinary innovation. The level of innovation with UAS technology promises to be breathtaking. Since Part 1 was published, I have found real life examples of similar UAS entrepreneurship. Beer was parachuted from UAVs to eager fans at a music festival in South Africa. The flying “hops helis” were dispatched to their locations via smartphone orders. Welcome to the revolution!

Any way you shake it, unmanned aircraft will define the future of aviation just as manned aircraft have in the past. The Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) recently released an economic study that predicts 30,000 UAS may be sold for agriculture purposes alone in 2015. Many more will be working overhead for other beneficial purposes, most of which have yet to be conceived. The successful manufacturers, services, and business models remain undefinable. But certainly, the U.S. and global economies will reap billions from the application of this stimulating new technology. Alas, the future is not yet written and there are significant threats to this burgeoning technology. In this article we will explore the tension between UAS and our constitutional protections of privacy and freedom of the press.

Not until 1989 was the commercial use of the internet was allowed. Few people, if any, in 1989 could have predicted the internet’s effect on the world economy and global societies. It was impossible to foresee the mind-boggling applications (both good and bad) of this technology. Facebook, Google, billions of webpages, RSS, Big Data, the Cloud, and the Apple App Store all arose because innovators could freely innovate and sell stuff using this new technology unhindered by the trammels of regulation. Countless inefficiencies in business and communication were eliminated by sending packets of information dancing across the global net. Today there are nearly 1.2 billion Internet-enabled devices used by 2.5 billion people across the planet. This foundational technology created a rolling boil of commercial and technological opportunities over the last three decades forever altering society and commerce. It is truly humbling!

UAS are similar. They are foundational in a sense because they will transform our national airspace into a platform for a wide berth of beneficial applications. As with the internet, it’s not possible to currently predict how UAS will be used over the next several decades. Innovators are tireless. Unforeseen applications will be discovered. The positive economic effects in dollars and jobs are more apparent each week…and ironically, more threatened. Of particular concern today is the potential erosion of our constitutional protections related to the right of privacy, protection from unwarranted search and seizure, and the freedom of the press. Excess fear and panic related to the rise of UAS threaten to hamper their adoption if ballarag regulations ensue.

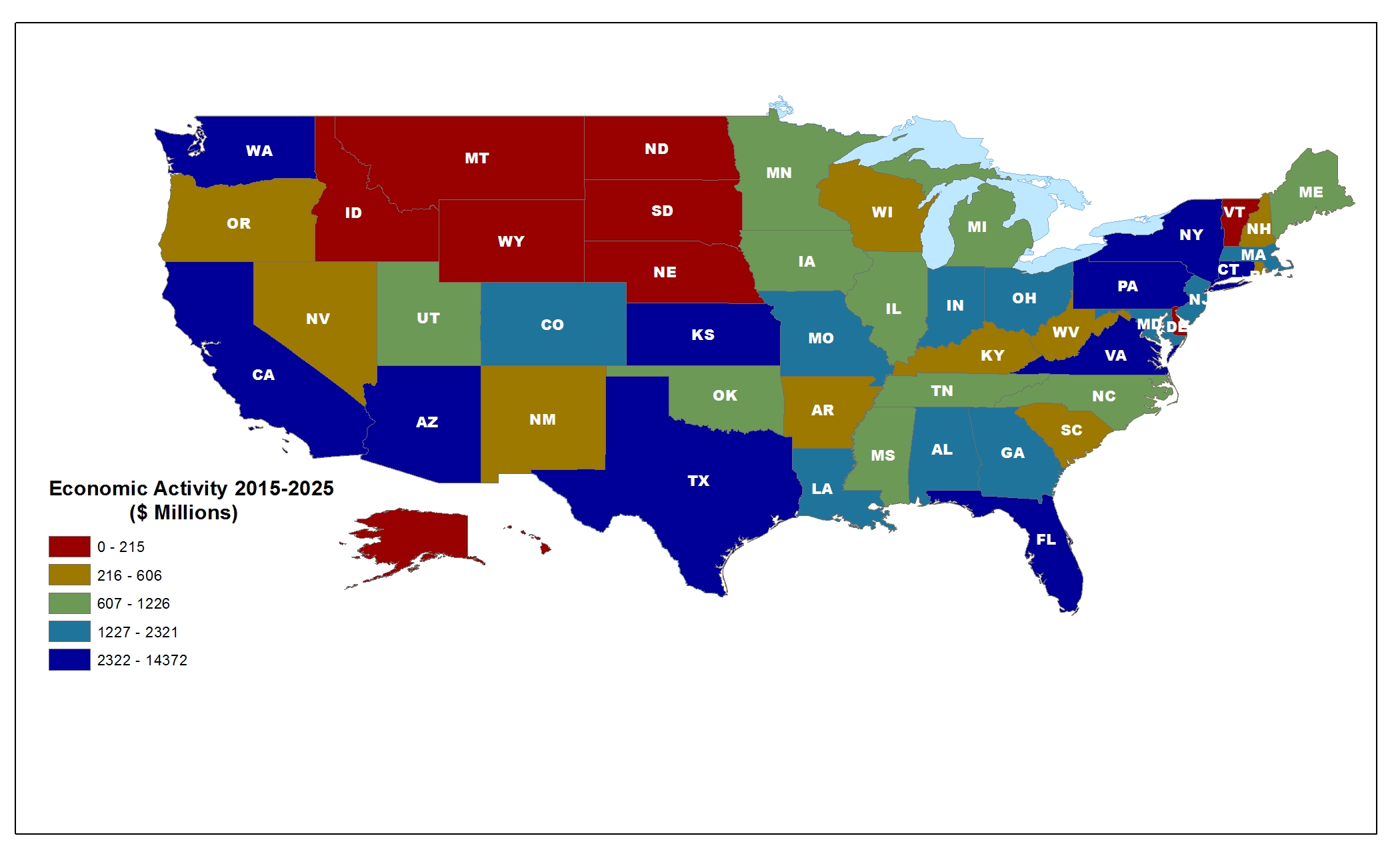

The Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) economic study predicts the economic impacts in each state in the United States.

The Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) economic study predicts the economic impacts in each state in the United States.

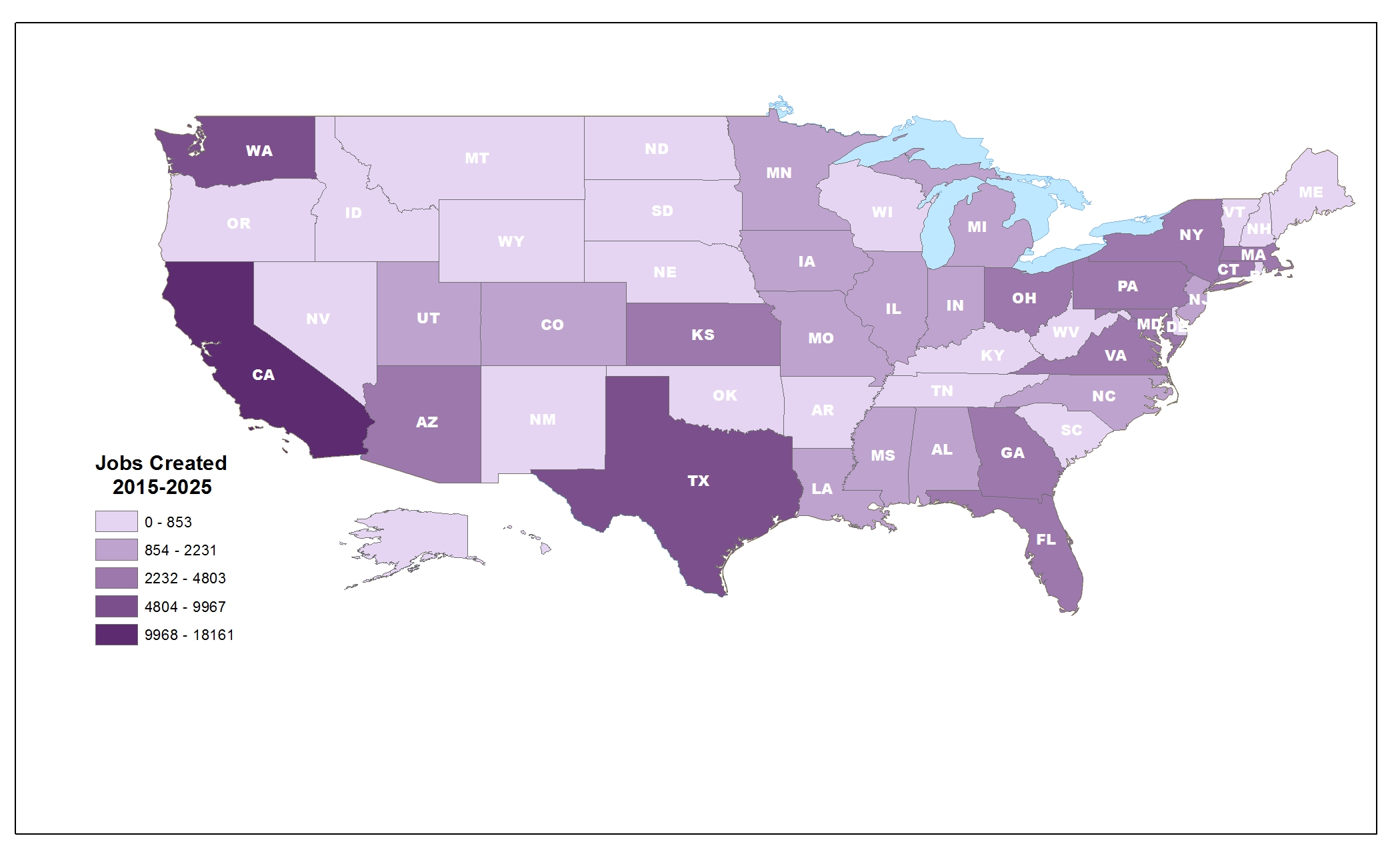

The Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) economic study predicts both the number of jobs to be created in the United States as well as their geography.

The Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) economic study predicts both the number of jobs to be created in the United States as well as their geography.

In the United States, the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states, “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated.” This concept of protection of an individual’s right to privacy is not outdated or obsolete by any means. The Fourth Amendment is as essential and valid today as the day it was included in the Bill of Rights over 220 years ago. The problem is the Fourth Amendment was designed and worded within the context of technology and capabilities in existence in 1776, not 2013. The framers of the Bill of Rights never envisioned UAS technology nor how its application could be used against individual citizens.

Historically, the greatest protections of privacy have always stemmed from the practical limitations of technology—that is, to spy on someone you had to follow them around. This was labor-intensive, expensive and time consuming. But small drones using inexpensive gyroscopes, accelerometers, GPS, and cameras have forever changed this equation. As practical barriers related to “remote sensing” fall away, the resulting privacy issues will assume heightened significance. Recent revelations about the NSA reaping and reading our nation’s electronic communications certainly does not help lessen the added fear of yet another “prying eye in the sky”. These are legitimate concerns, as is the threat that nefarious (and just plain stupid) individuals and entities will abuse or misuse UAS or any technology.

New technology often renders things previously thought impossible possible. Novel applications of technology often intersect with culture and tug at constitutional protections. UAS are no exception. It is true that our journeys across many cities are photographed continuously by cameras mounted on store fronts and poles. Many of us have received traffic citations from the robotic sensors used to record our driving infractions. Department stores are beginning to track our location within their aisles. “Black boxes” record our travels in our own cars using GPS.

My trek across a city is recorded. But my steps can be traced by others only after dozens of separate images scattered across a large number of private and public sensors are consolidated. Warrants are required to obtain many of those images. Additionally, I am aware of sensors along that path and I have no reasonable expectation of privacy in these public spaces. Our society has wrestled with much of this and, in some sense, has come to terms with this level of surveillance, i.e., in public or commercial spaces. Most Americans can live with this.

The ‘HoverMast’ developed by the Israeli start-up company Sky Sapience is an example of hovering camera technologies that are being developed.

The ‘HoverMast’ developed by the Israeli start-up company Sky Sapience is an example of hovering camera technologies that are being developed.

The “resolution”, “stealth”, and “persistence” of UAS constitute brand new threats to Americans’ privacy. UAS will provide the ability for private citizens and the government to put a single camera in the air over my head. I will not know it’s there. It cannot be observed. Manned aircraft are generally not flown below 1000’ above ground level.

When flying at high altitudes, powerful (and expensive) sensors are needed to produce high resolution imagery capable of revealing sensitive details like the identity of a human face. But UAS can be flown at any altitude, even just a few inches off the ground. Today, UAS equipped with commonly available sensors and flying at much lower altitudes can easily identify human faces and other crucial details that could potentially compromise our privacy.

Furthermore, consider the “stealth” nature of UAS. Traditional methods of aerial surveillance involve considerable “noise”. It’s not possible to position an aircraft near a home and not be heard. Small, electric-powered UAS, on the other hand, make virtually no sound and can hover unnoticed over your home for extended periods with no pilots to fatigue.

UAS “persistence” while surveilling is also a significant new concern. A single UAS equipped with sensors can record my movement throughout a city continuously. It can record and identify everyone I stop to talk with. Indeed, it can continuously record everyone’s activity in the city. Because all this data is on a single device one individual can reconstruct my entire trek from this one recording.

Questioning these as new threats to privacy is not unimportant. These UAS applications need to bask in the sunlight of public discourse well before our law enforcement institutions are allowed to use UAS for these purposes. Indeed, in the U.S. v. Jones in 2012, although the court ruled the authorities “trespassed” a man’s property by installing the GPS device in his vehicle without a warrant, the court left unanswered the constitutional question of whether the authorities violated the individual’s right of privacy by tracking his movements using GPS. The types of constitutional questions considered in this case, and not resolved, may have important implications for UAS used in our airspace. Bringing our country closer to one in which every move is recorded and scrutinized by the authorities is a Silurian idea that history has repeatedly demonstrated ends in statist control and the death of freedom.

If the privacy of citizens is eroded by UAS or any technology, a system of rules is needed to ensure Americans’ freedoms are protected so they can enjoy the promise of the technology. The best laws protecting privacy are technologically neutral. To the extent regulations are adopted that unnecessarily target a specific technology, the regulatory burden will become oppressive, confusing, and nescient.

For example, “Peeping Tom” laws prohibit people from looking into your bedroom window. Whether peeping is done by climbing a ladder, using a USB camera on the end of a broom handle, using a high resolution satellite sensor to peer inside, using a UAS hovering in my yard outside your window, or in the not-to-distant future, using “insect-sized flying sensors” from Walmart to fly unseen inside your home and record your activities, “peeping” (without a warrant) into your private space should be a crime. The best legislation would criminalize the act of peeping while remaining indifferent to the technology used to peep.

Today there are more than 40 states considering laws to limit UAS. Much of this activity is centered on concerns related to the protection of privacy. Certainly, it’s not too early to define the limits of law enforcement (without a warrant) to use UAS to surveil what has been considered the private activities of persons. But thoughtless bans on all uses of UAS by law enforcement would be unreasonable. For example, Olaeris is marketing a small “flying disc” equipped with speakers and sensors designed to be dispatched by 911 operators to a crime scene prior to law enforcement personnel to begin recording events, and even identify and dissuade criminals in the midst of their nefarious act. Some of the laws being considered may prohibit this life saving application of UAS technology.

“Existing laws and jurisprudence in America provide an important foundation upon which our society may accommodate this “unanticipated” technological development — much like has occurred with the Internet and mobile phones.” However, Kevin Pomfret from the Centre for Spatial Law and Policy suggests that, “the entire geospatial community needs to become more actively engaged in the ongoing discussions of what is a reasonable expectation of privacy from a geolocation standpoint given recent technological developments, otherwise laws, policies and regulations are likely to develop that will make it much more difficult and expensive for businesses and government agencies to do business.” Prior Supreme Court decisions and precedence are often poor predictors about how a particular decision will be made.

The warrantless observation of marijuana plants by authorities in a fenced backyard from 1000’ AGL was considered constitutional because anyone could fly over in an aircraft and observe the illegal activity, including the police (California v. Ciraolo, 1986 and Florida v Riley, 1989). The government was allowed to take aerial photographs of an industrial plant from navigable airspace using traditional remote sensing equipment without violating the Fourth Amendment on basically the same reasoning (Dow Chemical v U.S, 1986). Peering “inside” a home to detect an illegal marijuana-growing operation was ruled unconstitutional on the grounds that “advanced technology” not commonly available to the public was used to “search” inside a private space without a warrant (Kyllo v U.S., 2001). In other cases, observations at 200’ above ground level, well below navigational altitudes, did constitute illegal search (Colorado v Pollock).

This established case law provides a good foundation as we approach the age of Ubiquitous Remote Sensing, but clearly legislation and privacy rights will need measured definition in light of UAS advancements until our society is comfortable with this technology. Law enforcement and industry have already begun to adopt standards to guide the responsible use of UAS. The nation’s police chiefs have adopted a code of conduct for the use of drones and the disposition of information collected using them. This attempt at “self-regulation” does acknowledge the legitimate privacy concerns of the public and the need for a warrant prior to conducting flights that may intrude upon reasonable expectations of privacy. Earlier this year, the AUVSI released a similar “Code of Conduct” for the safe and responsible operation of UAS. These actions by trade and law enforcement groups are constructive and may provide the needed framework to usher in the safe, responsible use of UAS.

The nation’s police chiefs have adopted a code of conduct for the use of drones and the disposition of information collected using them.

The nation’s police chiefs have adopted a code of conduct for the use of drones and the disposition of information collected using them.

There will always be those who work outside of the law. The bulk of future offenders can be marginalized by existing laws and sensible regulation, but also by insurance (after the UAS insurance risk assessment and products mature). Insurance can be used effectively to marginalize those who will use UAS to violate others constitutional rights (The Path to UAS Commercialization, Darryl Jenkins, August 2013, AUVSI 2013 Conference Proceedings (Subscription)). The UAS operator responsible for recently crashing a small aircraft into a crowd of spectators at a Bull Run festival in Virginia may endure such “marginalization” because of liability exposure.

Certainly, social norms will evolve and adapt to an airspace replete with flying robots. Overreaction to “potential” violations of privacy with rampallian regulations will enervate and stupefy the future potential of UAS. We should not preclude UAS innovation today with overly prescriptive privacy regulations, but instead, encourage innovation and address tangible harms as they develop. Withholding regulation until after our nation has real experience using UAS will ensure a fertile ground in which innovation can flourish as it did with the Internet and mobile phones industries since the 1990’s.

Of course, on the flip side of “privacy” are our constitutional protections of free speech and a free press. Private entities are not bound by the Fourth Amendment restrictions that apply to the government. The key constitutional question is the extent of a citizen’s First Amendment (freedom of speech and of the press) privilege to gather information.

How long will it be before a journalist, paparazzo or stalker flies a UAS into the “private spaces” (whatever that might be) of another person? Does a journalist have the “right” to “hover over” those injured at the scene of a traffic accident and take high resolution images of the victims without their consent? Do paparazzi have the right to use UAS and “lock onto” a movie star in order to persistently and silently follow and photograph them? Do journalists have the first amendment right to gather news by using UAS to monitor wireless signals of individuals or organizations? If I fly my personal UAS near your property at treetop heights do I have the right to post on Facebook a picture of a document photographed on your patio?

In the end UAS are nothing more than machines or tools that can be used for a variety of purposes and in a variety of ways. The technology is generally not the threat to our constitutional liberties. The operation and use of that technology, and the information it captures, is the actual threat. This intersection of my right to privacy and your right to take pictures (or record sound) will most assuredly be fleshed out in the coming years.

This discussion of privacy and UAS intersects the FAA Modernization and Reform Act (FMRA) of 2012. This legislation instructed the FAA to “provide for the safe integration of civil unmanned aircraft systems into the national airspace system as soon as practicable, but not later than September 30, 2015.” The FAA is responsible to ensure all private and commercial airline passengers continue to fly safely in the skies over our nation alongside unmanned vehicles. The FAA’s commitment to get right the integration of UAS into national airspace is laudable. The FAA is the best group to insure safe travel in our airspace.

Our national airspace is arguably the safest in the world due in large part to the FAA’s oversight. They could be, however, the worst group to handle the extremely complicated and legal aspects of privacy. How and why they have staked out a position to ensure UAS are used in ways that do not compromise constitutional protections of privacy is still unclear.

Congress’s charge to the FAA was simply to ensure the safe integration of UAS into the national airspace. There are no references to “privacy” in the FMRA. As previously discussed, there already exist federal, state, and other laws that protect an individual’s right to privacy. The FAA should leave questions of UAS privacy to other institutions and focus on what they do best … “provide the safest, most efficient aerospace system in the world”.

Our rights to free expression and privacy are not absolute. As citizens of the United States we have an obligation to be constantly vigilant and informed so that we remain protected against official depredations. Equally important is striking a balance with protections of our constitutional rights and not hindering the innovation and application of a new technology by over-regulating UAS out of fear or misinformation. At risk are the enormous societal and economic opportunities inherent with this exciting new technology.

Be sure to read the first installment, if you haven’t already: The Rise of the [Geospatial] Machines Part 1: The Future with Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS)

In Part 3 of this series, we will review new advances in UAS technology and some of the exciting opportunities in the next 5-10 years that promise to transform a multi-billion dollar segment our economy and much of the geospatial markets.