SDIs are being developed to help address environmental concerns, disaster preparedness and emergency responsiveness there are other possibilities for benefiting from SDIs, namely regional competitiveness. This could mean public sector organisations who are currently experiencing budget cuts across the board could use activities relating to geospatial data to minimise budget cuts or maintain existing budget levels. This is because their activities provide a positive contribution to the regional economy, especially where the overriding objective is to build a knowledge economy.

SDIs are being developed to help address environmental concerns, disaster preparedness and emergency responsiveness there are other possibilities for benefiting from SDIs, namely regional competitiveness. This could mean public sector organisations who are currently experiencing budget cuts across the board could use activities relating to geospatial data to minimise budget cuts or maintain existing budget levels. This is because their activities provide a positive contribution to the regional economy, especially where the overriding objective is to build a knowledge economy.

At the end of 2009 1Spatial participated in the 24th International Cartographic Conference (ICC) in Santiago, Chile. Steven Ramage presented on Spatial Data Infrastructures (SDIs) and regional competitiveness. This presentation was based on 1Spatial’s involvement in the European Spatial Data Infrastructure best practice Network (ESDIN), the Infrastructure for Spatial Information in Europe (INSPIRE) and other SDI initiatives across the globe. The basic tenet is that although SDIs are being developed to help address environmental concerns, disaster preparedness and emergency responsiveness there are other possibilities for benefiting from SDIs, namely regional competitiveness.

This could mean public sector organisations who are currently experiencing budget cuts across the board could use activities relating to geospatial data to minimise budget cuts or maintain existing budget levels. This is because their activities provide a positive contribution to the regional economy, especially where the overriding objective is to build a knowledge economy. Later in this article there is some evidence that funding has been supplied to improve geospatial data supply chains and increase the associated data quality – these could be taken as a surrogate measure of regional competitiveness.

The purpose of the presentation was to:

Background

This short article will complement the ICC 2009 presentation by providing background to the thinking. Some of the initial ideas came from discussions with Dr. Max Craglia from the EC Joint Research Centre (JRC). Along with the Directorate General for the Environment and the European Statistical Office (Eurostat), the JRC was responsible for developing the INSPIRE Directive which came into force in 2007. The JRC now has particular responsibility for the various Implementing Rules and the work being done by Thematic Working Groups on the 34 INSPIRE themes.

The discussion was broadly related to the measure of success associated with an SDI, for example is a region more successful because it has an SDI or does it have an SDI because it is successful? This then begs the question, how do you measure SDI success? One approach could be to use a Multi-view SDI Assessment Framework. A team from Benelux and Cuba assessed 11 National SDIs in American countries and the Netherlands as part of this approach. They simultaneously applied four assessment approaches instead of one for a more complete and more objective SDI assessment result. These included the SDI-Readiness approach, clearinghouse suitability, INSPIRE state of play and the organisational approach.

International activities

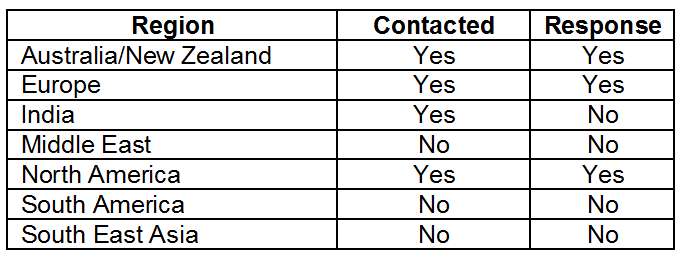

For the ICC presentation a number of international SDI experts were requested by 1Spatial to provide information from regions across the World1. The table below highlights the regions that were contacted and whether or not they provided information to 1Spatial.

The SDI experts were asked to provide information relating to perceived or actual economic benefits arising from SDI activities in their region. A sample of the responses from Australia/New Zealand, Canada and the USA are included here:

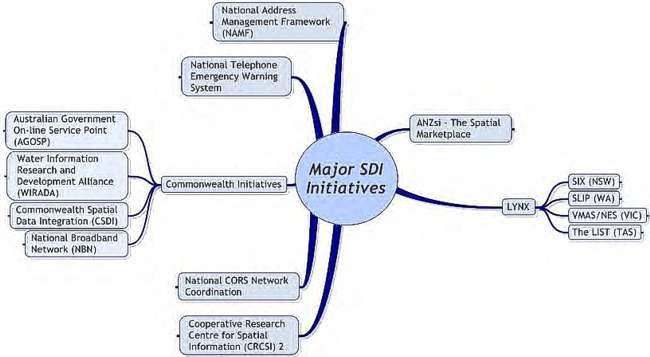

Australia/New Zealand – more than 10 years ago the Australia New Zealand Land Information Council (ANZLIC) produced an SDI discussion paper. However, it seems that regional SDI activities are still at a nascent stage today in the region. ANZLIC is currently promoting and supporting the Australia and New Zealand Spatial Infrastructure (ANZsi), which in turn has very strong connections to the Cooperative Research Centre for Spatial Information (CRCSI) and PSMA Australia’s LYNX initiative.

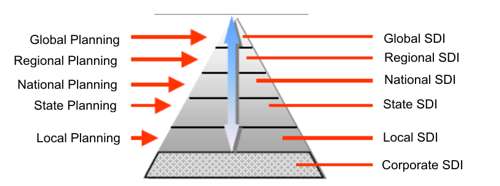

ANZLIC stated that New Zealand and Australia could benefit from better management of their spatial information starting from the national level and working down to the local level. The approach appears to be more bottom up than top down where sub-national activities are driving the overall national framework in Australia with activities picking up in New Zealand through involvement from Land Information New Zealand (LINZ). See Figure 2 for an example of SDI activities in Australia.

A Price Waterhouse Benefit Study2 in 1999 estimated a benefit: cost ratio for data usage of approximately 4:1. This means that for every dollar invested in producing spatial information, $4 of benefit was generated within the economy. More recent figures (2008) can be found in some ACIL Tasman reports.3.

This type of information is invaluable in terms of regional competitiveness statements and contributions to the economy in general. Benefits are also listed across spectrum of economic activities ranging from the operation of electricity, gas, water utilities to projects involving agriculture, mining and environmental management.

Canada – a national partnership program led by Natural Resources Canada promotes the use and growth of the Canadian Geospatial Data Infrastructure (CGDI). During the past 10 years, this program — GeoConnections — has evolved over two consecutive phases. In the first phase (1995-2005), the programme collaborated with stakeholders to begin developing the CGDI.

Now the programme is in its second five-year phase (2005-2010). The focus has shifted to co-funding projects aimed at helping decision-makers use the CGDI as an operational asset in four priority areas: public health, public safety and security, the environment and sustainable development and matters of importance to Aboriginal communities.

The co-funding mechanism on which GeoConnections is based has been a key factor in its success to date. For example, by collaborating with stakeholders on projects during the first phase, the program was able to leverage its budget of $60 million into $170 million of investments in the CGDI.

The benefits of the programme to Canada are numerous. The functionality the programme delivers (e.g. partnerships, information sharing and interoperability) has widened and improved the use of Canadian geospatial data. The made-in-Canada solutions GeoConnections has worked with stakeholders to develop have asserted Canadian leadership in geospatial information systems and strengthened the regional brand. The efficient and effective decision-making enabled by new applications is yielding socio-economic benefits, and improvements are beginning to emerge in Canada’s international competitiveness, productivity and economic efficiency…

A respondent to a recent survey wrote, “GeoConnections and the work it has done have allowed us to almost quadruple our sales from three years ago. Over 80% of our 2009 sales are export and without the reputation of GeoConnections and the people involved, we would not be able to point to success within Canada in policy, approaches to framework data and the like.”

In summary, this collaboration has assembled a valuable Canadian geospatial public asset that is already delivering returns on the nation’s investment and is expected to have a major payoff in the future.

Europe – a couple of examples have been picked from 2 of the 27 EU Member States. In the UK for example, there was a Location Strategy document created to outline the challenges and plans for the UK SDI. In paragraph 28 it talks about key aspects that can help make the UK Location Programme more efficient:

At the Global Spatial Data Infrastructure (GSDI) 11 Conference in Rotterdam in his paper ‘The Danish Way: Development of the Danish SDI through binding collaboration’, Jesper Jarmbæk, Director General of KMS Denmark highlights these points around cooperation and avoiding duplication.

“Just as there are efforts such as the FOT collaboration to avoid duplicate work at the national level, it is also important to avoid duplicate work at a European level.”

USA – For the last two years, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has supported a management/budget initiative known as the Geospatial Line of Business (LoB). LoBs have been created to force coordination and develop a shared investment portfolio among multiple federal agencies. Geospatial content is the common thread and it cuts across other lines of business (public safety, tax assessment, land management, etc.)

“In review of potential benefits from this overt coordination, especially on investments and ‘savings’, the main financial benefit to geospatial coordination is through cost-avoidance rather than cost-savings.”

Douglas D. Nebert, Senior Advisor for Geospatial Technology,

System-of-Systems Architect, FGDC Secretariat

Cost avoidance – through single data collection and assessment for multiple uses – cooperative data acquisition and free exchange between members avoids any multiplier cost of buying the data once per agency. In terms of potential cost-savings, in commercial markets for geospatial data that could be licensed for pan-governmental use, typically there are discounts for such a bulk purchase. This means a vendor has a single point of contact and less overhead, the agency sees a reduced cost than if it negotiated a price independently.

Regional coordination and competitive advantage offer the following:

Agreeing-to-agree on a small set of standards in-play allows more effort on other core mission activities. This is a key statement from Doug Nebert at FGDC:

“It is important for agencies to not be threatened by losing funds if they demonstrate savings, but to be required to apply them to improve the speed or quality of services. Otherwise, there is little incentive for an agency to save money if the (often notional) savings are removed from their budget for future years.”

EU Intent

The Lisbon Strategy targets low productivity and the stagnation of economic growth in the European Union (EU). It was adopted for a ten-year period in 2000 in Lisbon, Portugal by the European Council. It aims to “make Europe, by 2010, the most competitive and the most dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world”.

From Europe’s Digital Competitiveness Report, the main achievements of the i2010 strategy 2005-2009 were related to the following:

“The World Wide Web, the mobile GSM standard, the MPEG standard for digital content and ADSL were all invented in Europe.”

According to this report Europe is the World leader in broadband Internet with 114m subscribers. This means there is a plan for higher usage of services, e.g. sharing and creating new content. This could be geospatial.

The Competitiveness and Innovation Framework Programme (CIP) encourages competitiveness of European enterprises, principally targeting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). It encourages take-up/use of information and communications technologies (ICT) and helps develop the information society. With a total budget of €3.6 billion the programme runs from 2007 to 2013. The most relevant CIP programme for SDIs is:

In the context of the Lisbon Strategy, i2010 is emphasising contribution of ICT to growth and jobs. The “i” in i2010 stands for information space, innovation and investment and inclusion. It focuses on a few policy priorities:

It could be argued that INSPIRE is creating the single European geoinformation space.

How ESDIN fits

Over the last two years, more than €2 billion of European Union funds have been committed to Information and Communication Technology (ICT) research projects. This investment has been made with a view to making Europe more competitive on a global scale. This investment can also benefit those working in the field of Spatial Data Infrastructures. Primarily in Europe via the funding and direct involvement in ESDIN (European Spatial Data Infrastructure Network), but also globally for those tracking ESDIN progress and lessons learned.

The ESDIN eContentplus project, co-funded by the European Union sets out to tackle practical elements of the INSPIRE Directive (Infrastructure for Spatial Information in Europe). It will address the INSPIRE challenges by testing the theory of integrating National Spatial Data Infrastructures (NSDIs) to provide Europe with a framework of geographic reference information or in other words a European Spatial Data Infrastructure for which INSPIRE is the legal instrument. ESDIN will provide useful information to the geospatial community as a whole, in terms of best practice around SDIs. The reasons for ESDIN receiving funding from the European Commission under the eContentplus programme can be translated into competitiveness as part of the European ICT agenda.

As the only UK technology provider working in ESDIN, 1Spatial is helping the consortium to develop best practice for geospatial data management. Co-ordinated through twelve work packages the project deals with methodologies in two of these for Metadata and Quality, and Data Maintenance and Business Processes in National Mapping and Cadastre Agencies.

Approach for geospatial data management

ESDIN addresses some long-standing industry problems, such as data consistency and integrity, by looking at possibilities for online data quality validation. It also looks into some specific data maintenance topics of interest to data providers, such as:

Cross-border data consistency methodologies for edge-matched maintenance; important for combining spatial data of adjacent regions seamlessly from different sources;

Stable Unique Identifiers (UIDs); workable at a European level in a data maintenance framework for regional or national data holdings;

Incremental updates deliveries at a European level; assessing methodologies and best practice for change-only updates.

ESDIN will help Member States, candidate countries and EFTA States (European Free Trade Association) to prepare their data (and maintenance processes) for INSPIRE Annex I data themes and improve access to them. Specifically the project will:

• Aggregate data via development of web based services for INSPIRE themes at different levels of resolution from European to local level;

• Implement services that will support the aggregation of ‘interoperable’ data in a more cost effective and efficient way;

• Build sustainable best practice networks to ensure the organisational development necessary to achieve the goals of the project and its continuation afterwards;

• Spread best practice in the integration of local (large scales) reference information with pan-European (medium/small scales) reference information, and interoperability with other data themes;

• Test INSPIRE Implementing Rules and specifications in a live operational environment and recommend improvements where identified.

ESDIN is working on best practice for integrating the National Spatial Data Infrastructures (NSDIs) of Member States to help support the European SDI. This will ascertain if users can access and share geospatially referenced data for a variety of date themes at a European or local level.

Conclusions

Spatial Data Infrastructures require significant investment and those backing that investment will be determining the success of their SDI based on a number of factors. In particular, the accessibility of geospatially referenced data for decision-making in the event of natural disasters like flooding across borders. However, there is also a wider business imperative relating to SDIs and in the European context this means ICT competitiveness. In order to establish and maintain its leadership in key ICT areas Europe has to do more in research and innovation in ICT. Investing in projects such as ESDIN will support competitiveness and help build the European knowledge economy through geospatial data management best practice.

Possibly where SDIs aim at improving the geospatial data supply chain and speed up the process from data capture to delivery, i.e. usefulness of data for analysis, planning and decision making, they merit increased government funding. By making geospatial data complete and consistent this can lead to such funding mechanisms being created to support regional competitiveness and benefit the economy as a whole. This data quality aspect is a major consideration in supporting and facilitating SDIs, and it should be tackled at various stages across the supply chain to ensure it is an iterative and ongoing process.

So depending on your point of view, regional competitiveness through geospatial data providing economic benefit could mean continued or additional funding, or even just survival of a government function or organisation. Do you have any ideas about how your organisation can be more competitive?

More information:

http://www.csdila.unimelb.edu.au/publication/books/mvfasdi.html