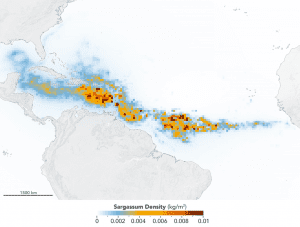

Scientists used NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on Terra and Aqua satellites to discover the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt (GASB), which started in 2011. It has occurred every year since, except 2013, and often stretches from the west coast of Africa to the Gulf of Mexico. (Credit: NASA/Earth Observatory. Data provided by Mengqiu Wang and Chuanmin Hu, USF College of Marine Science)

An unprecedented belt of brown algae stretches from West Africa to the Gulf of Mexico—and it’s likely here to stay. Scientists at the University of South Florida in St. Petersburg’s College of Marine Science used NASA satellite observations to discover and document the largest bloom of macroalgae in the world, dubbed the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt, as reported in Science.

Based on computer simulations, they confirmed that this belt of the brown macroalgae Sargassum forms its shape in response to ocean currents. It can grow so large that it blankets the surface of the tropical Atlantic Ocean from the west coast of Africa to the Gulf of Mexico. In 2018, more than 20 million tons of it floated in surface waters and became a problem to shorelines lining the tropical Atlantic, Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, and east coast of Florida, as it carpeted popular beach destinations and crowded coastal waters.

“The scale of these blooms is truly enormous, making global satellite imagery a good tool for detecting and tracking their dynamics through time,” said Woody Turner, manager of the Ecological Forecasting Program at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

Chuanmin Hu of the USF College of Marine Science, who led the study, has studied Sargassum using satellites since 2006. Hu spearheaded the work with first author Dr. Mengqiu Wang, a postdoctoral scholar in his Optical Oceanography Lab at USF. The team included others from USF, Florida Atlantic University, and Georgia Institute of Technology. The data they analyzed from NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) between 2000-2018 indicates a possible regime shift in Sargassum blooms since 2011.

In the satellite imagery, major blooms occurred in every year between 2011 and 2018 except 2013. This information, coupled with field measurements, suggests that no bloom occurred in 2013 because the seed populations of Sargassum measured during winter of 2012 were unusually low, Wang said.