Throughout two contentious California lawsuits to uphold Public Records Act (PRA) access to county GIS parcel basemaps, many GIS professionals got involved with this issue. They informed themselves, they spoke out, they monitored online discussion groups and contributed opinions. Some GIS professionals used their expertise to analyze the content and structure of contested basemaps; some devised techniques for importing obscure-format files into standard GIS-compatible format; some provided useful illustrations and testimony to the courts.

Throughout two contentious California lawsuits to uphold Public Records Act (PRA) access to county GIS parcel basemaps, many GIS professionals got involved with this issue. They informed themselves, they spoke out, they monitored online discussion groups and contributed opinions. Some GIS professionals used their expertise to analyze the content and structure of contested basemaps; some devised techniques for importing obscure-format files into standard GIS-compatible format; some provided useful illustrations and testimony to the courts.

A growing number of individuals in our GIS community added their names as co-signers to various Amicus (friend of the court) briefs, that explained geospatial concepts to the judges. 55 individual GIS professionals co-signed the GIS Amicus brief in the Santa Clara case. That number grew to 72 co-signers supporting Sierra Club’s appeal in the Orange County case, and topped off with 212 individuals co-signing the Amicus brief to the California Supreme Court, where Sierra Club proved victorious. These briefs helped the Justices decide whether GIS databases should be exempted as “software,” whether GIS-compatible file format was required to satisfy PRA demands, and what impact restricting access to government geodata might have on the geospatial community and our democratic society.

Individually, we have the knowledge and skills to influence public policy. Additionally, when we collaborate together through professional organizations, we gain power beyond our individual strengths, in two ways. First, 23 GIS organizations co-signing the Amicus brief confirmed its analysis and opinion represented a professional standard recognized by the vast majority of GIS experts. Second, GIS associations educate and promote geospatial-related public policy issues by publishing position papers, providing workshops, and organizing conferences. One outstanding representative of our professional community is the National States’ Geographic Information Council (NSGIC).

A great majority of NSGIC’s members, state Geographic Information Officers and GIS Councils, support the notion that governmental geodata must be accessible to the public without fees or licensing restrictions that limit such access. NSGIC’s Board voted to co-sign the Sierra Club Amicus brief, and further, initiated a Data Policy committee to formulate solutions to the underlying problem that causes some public agencies to sell their geodata. Resolution occurs when public agencies know how much value their GIS’ data analyses contribute to the agency’s overall operation; then, budgetary funding for ongoing support becomes pro-forma, much like other enabling infrastructures.

A great majority of NSGIC’s members, state Geographic Information Officers and GIS Councils, support the notion that governmental geodata must be accessible to the public without fees or licensing restrictions that limit such access. NSGIC’s Board voted to co-sign the Sierra Club Amicus brief, and further, initiated a Data Policy committee to formulate solutions to the underlying problem that causes some public agencies to sell their geodata. Resolution occurs when public agencies know how much value their GIS’ data analyses contribute to the agency’s overall operation; then, budgetary funding for ongoing support becomes pro-forma, much like other enabling infrastructures.

NSGIC’s first workproduct, “Geospatial Data Sharing Guidelines For Best Practices (PDF),” is an easy-to-read, four-page handout, designed to inform and persuade public agency managers, governing boards, and legislative councils. The brochure avoids technical “geospeak,” enabling GIS professionals to present an authoritative document to decision makers in language they can understand.

The Guideline begins with, “open sharing of geospatial data is in the best interest of our communities, states and nation.” It describes the value of accessible geodata, and dispels several myths about selling government geodata (data sales really doesn’t contribute much to an agency’s revenue). The brochure presents a Data Policy Vision in which recognizing the benefits of unencumbered geodata distribution will justify supporting an agency’s GIS. The message is:

• Geospatial data returns more value to an agency than its cost.

• As more people using geodata, more value is accrued.

• Agencies with data sharing policies have more economic development than agencies with data selling policies.

• To support GIS operations, an agency should:

o Track the costs saved

o Track the added revenue

o Allocate a portion of these benefits to GIS operations

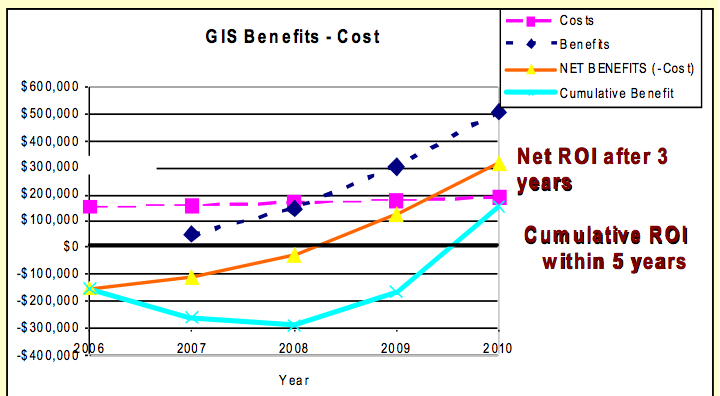

But how can an agency track and calculate its GIS costs and benefits? NSGIC’s most recent guideline, “Economic Studies for GIS Operations” explains, with examples. Return On Investment (ROI) and Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) techniques are described for comparing the costs and net benefits of geospatial operations, in both financial (net present value, internal rate of return) and temporal (time period to recoup the investment) terms.

Quantitative and qualitative analyses consider both tangible and intangible benefits. Most usefully, eight ROI/CBA studies are reviewed with links to the actual documents, giving readers an opportunity to learn the details. These methods enable GIS projects to be prioritized within the context of an agency’s total budget, and they provide rational arguments for budgetary support of geospatial operations without having to sell public records.

The synergy of collaboration and the mutual enthusiasm of shared ideals, within the credibility of well-vetted organizations, enable us to affect public policy. Yet ultimately, the organizations, the committees, and the implementation of their recommendations succeed because individual GIS professionals care enough as citizens to participate.