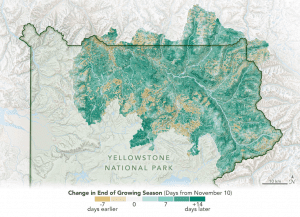

A study using data from two NASA Earth science satellites reveals that the season for vegetation growth has been getting longer in Yellowstone National Park. Likely a result of climate change decreasing the severity of winters and warming average temperatures overall, this effect on the productivity of grasslands has contributed to the growing number of bison in the park. (Credit: Joshua Stevens/NASA Earth Observatory)

The bison population has grown rapidly during the last two decades in Yellowstone National Park. This creates complex situations for wildlife managers when the animals follow good grazing opportunities beyond the boundaries of the park and come into contact with surrounding communities. A NASA study has now found a link between climate change effects on the productivity of grasslands and the proliferation of bison in Yellowstone, by compiling 20 years of data from two NASA Earth science satellites. The work also shows how the same data, available in near-real time, can aid the park’s conservation efforts by providing daily maps of green grass cover that help forecast the movements of bison.

The research project looked specifically at how long the growing season lasts in Yellowstone, from snowmelt in spring to first snowfall in autumn, and the vegetation that covers the land in between. The satellite data revealed that the season for vegetation growth has been getting longer, likely a result of climate change decreasing the severity of winters and warming average temperatures overall.

Studying national parks is helpful for this type of climate research, because human land use is restricted in these spaces. With little interference from people since Yellowstone was founded in 1872, scientists are better able to isolate climate change as a factor in any changes they observe there.

With the growing season getting longer across large areas of Yellowstone, the bison have had more opportunity to feed on grass, which has likely helped their population grow. But, as they pursue the best grazing spots throughout the season, they sometimes leave the protected area of the park. Tracking grassland growth can provide a clue to the bison’s next move.

The National Park Service originally approached NASA 10 years ago, looking for insight into patterns of growth across Yellowstone’s grasslands. At that point, there was enough long-term, daily satellite data to make a good start on meeting those needs, but to draw really confident conclusions about climate effects, scientists needed to look at a longer period.

An instrument called MODIS, short for Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, now has a record 20 years long. Mounted aboard two different satellites (Terra, launched in 1999, and Aqua, launched in 2002), it has been able to view the entire surface of Earth not covered by clouds every day for two decades. For the climate study, Potter compiled data from this entire stretch—the first time such a long run of daily updates has been compiled and analyzed for this National Park. With the data analysis performed, Yellowstone’s wildlife managers can now check maps tracking the daily change in snow-covered area and the vegetation growth that follows. They’ll use those data to try to anticipate where and when confrontations between bison and human communities are likely to happen and prepare the most appropriate conservation actions at the park boundaries.