Everywhere they turn these days, manufacturers of all-in-one GPS devices run into bad news.

Early in August 2015, Trimble stock reached $19.01 per share, down 44.8 percent from a year earlier. Sales of Garmin personal navigation and auto devices fell 11 percent in the fourth quarter of 2014, a decline consistent with those of recent years and one projected to be matched in the future.

The trend has a definite starting date: June 9, 2008, when Apple introduced its iPhone 3, with a GPS chip. During the first weekend the public could buy the device, July 11-13, 2008, Apple sold 3 million iPhone3s. In October of that year, Google introduced its Android operating system, adding Google Maps and a navigation program to a smartphone that had just gotten smarter.

The impact was quick. In 2007, Garmin posted record revenues, commanded 50 percent of the GPS industry’s American market, was the hot Christmas gift and seemed on the cusp of being the Xerox of location-based devices.

Seven months later, the company’s stock price had dropped 50 percent.

“Demand for dedicated GPS units is slowly dwindling,” wrote Sam Mattera in July 2015 in The Motley Fool, an investment blog. “Smartphones, equipped with a variety of robust mapping services, rendered them obsolete years ago. The market has been slow to react, but it seems unlikely that these devices will exist for too much longer.”

The above-cited figures indicate market reaction is picking up steam.

So, too, is the market for smartphones. About two-thirds of American adults own one, up from one-third in 2011. Nearly half own tablet computers, and their numbers are growing. There are 2 billion smartphone users worldwide today, and their number is expected to grow to 6 billion by the end of the decade, according to GMSA research.

Apple claims to sell 378,000 iPhones every day in a world in which 371,000 babies are born over that same 24 hours.

Those iPhones and their Android brethren have sent digital cameras, watches, music devices and personal data assistants to museums—and they’re being joined by laptop computers as smartphone users turn to their devices for Internet access. All-in-one GPS devices are joining the migration toward obsolescence.

The Department of Defense’s $15 billion investment in a NAVSTAR GPS constellation that can determine position and time of day anywhere in the world has spawned a $75 billion-a-year industry of commercial hardware and software to take advantage of it.

From its first devices—Garmin’s GPS 100AV, costing $1,000 in 1981; Trimble’s surveying and maritime instruments in 1984, and others—companies carved out an ever-growing market for first military, then civilian customers.

Some companies, particularly those operating in precision-measurement surveying and cartography, integrated vertically, selling and servicing proprietary devices and training their users. The GPS community drove markets for its products and their users by teaching new and different ways to use GPS data. The GPS pioneers, dominated on the personal device end by Garmin and TomTom and on the proprietary side by Trimble, Leica and Topcon, created a controlled environment that seemed boundless in its potential.

And then Apple invented the iPhone3 and, shortly thereafter, tablet computers with similar GPS capabilities. With Android added to the mix, the smartphone was invented. But was it smart enough for widespread GPS use, particularly beyond such tasks as telling you where to find a restaurant?

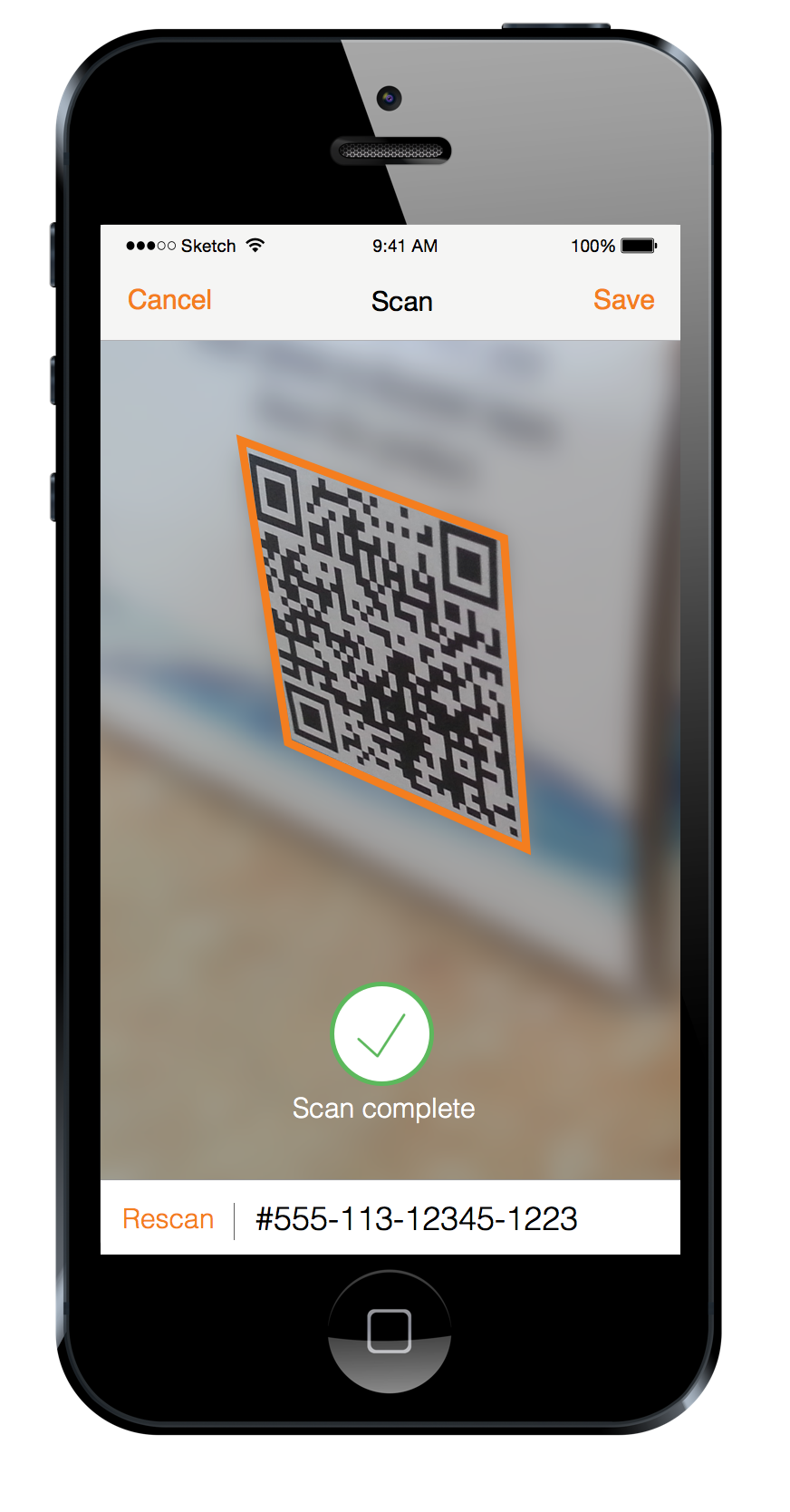

Powerful smartphone apps speed data collection with automatic code recognition tied to a location.

Powerful smartphone apps speed data collection with automatic code recognition tied to a location.

Turns out it was.

Companies—many of them manufacturers of GPS devices—couldn’t wait to test the smartphones, and some of them were found wanting, at least at first. In some cases, the Garmins and Trimbles of the world dismissed the upstarts, much to their eventual chagrin. Garmin co-founder Min Kao told Forbes he wasn’t concerned about them because of “high barriers to entry,” and he was reluctant to believe they could successfully integrate GPS signals from satellites with cartographic quality software and navigation features on the smartphone.

By 2013, the company had lost 70 percent of its value and was becoming more known for fitness watches than other GPS devices.

A 2009 study published by University of New Mexico professor Paul Zandbergen showed that the iPhone3 had an average accuracy of 8 meters, compared to the 1-5 meters of the all-in-one GPS devices. But subsequent smartphones, with better antennae and batteries, were closer, and when linked by Bluetooth to such GPS receivers as Bad Elf, SXBlue, FastField, etc., were very close to spot on.

Recent tests have shown that the smartphone can deliver GPS accuracy well within a meter of the all-in-one device, but long before that, industry began pondering the billions it was spending on GPS and wondering if the price of that last meter was too high.

Markets for proprietary GPS devices persist in construction, surveying (particularly cadastral surveying in developing countries), aviation and agriculture, in which the devices operate machines in “precision farming.”

But even those markets may be impacted the way personal GPS devices of Garmin and TomTom were impacted by smartphones and tablet computers, married to external GPS receivers that offer additional power and data storage, along with more accuracy. And while builders are generally dependent on precise geospatial measurements, commercial site selection often is pushed by smartphone-driven data collection to determine market potential and customer flow.

Other industries have decided that the degree of precision in the data generated is not as critical as the speed and cost involved in getting that data: utilities, oil and gas, emergency response, water management, municipal, retail and others. In many ways, those industries have taken their lead from the military—and in turn have done research leveraged by the military, which is moving toward equipping soldiers with smartphones, in effect making every soldier a sensor.

The retail field is an emerging market for smartphone and GPS capability, taking advantage of a concept called “geofencing” to track customers near a store looking for a sale. Macy’s flagship department store in New York offers a geolocation app to help guide customers around the giant facility. Other retail concerns, along with their suppliers, are finding new and imaginative ways to use GPS capability in manufacturing and marketing, going miles farther than they ever did with all-in-one devices.

The degree to which smartphone and tablet GPS technology has been disruptive can be seen dramatically in road operations that once were charted by proprietary GPS devices. Many trucking firms have shifted to smartphone tracking and are finding such an impact on Return on Investment (ROI) that proprietary tracking devices for commercial vehicles are expected to disappear in some regions and diminish greatly in others by 2022, according to research in Europe.

Ongoing tests of the GPS capability of smartphones, conducted by Community Health Maps, affirmed their accuracy and posited two questions that organizations must ask when considering field GPS data collection devices: “How accurate are they?” and “What kind of accuracy will meet the needs of my project?”

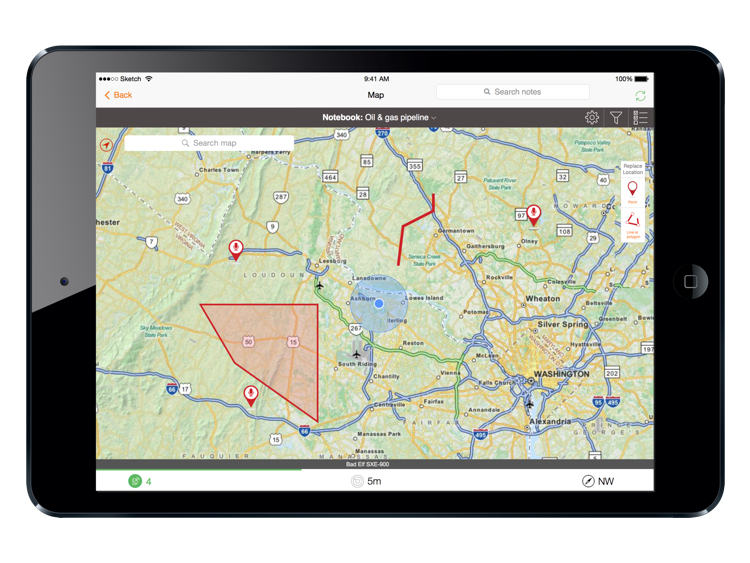

GPS-enabled apps allow users to monitor remote workers and projects in real time.

GPS-enabled apps allow users to monitor remote workers and projects in real time.

Pew Research indicated that the average smartphone and tablet computer has 41 applications and that three-quarters of those are location based. Nielsen research added that 76 percent of men and 72 percent of women use location-based applications regularly, and those numbers are not lost on companies that have a field force that once spent time training to use all-in-one GPS devices.

What if the work force was already trained?

From that question, a phenomenon has arisen called Bring Your Own Device (BYOD). Its cousin is CYOD (Choose Your Own Device). Industries have adopted those acronyms (CYOD tends more toward companies buying one for the worker) in growing numbers and finding that employees are more productive when using familiar devices in the field to do their work.

Aberdeen Research indicated that BYOD employees were 5 percent more productive, CYOD 9 percent more, and companies were saving training money and time. Those companies also better liked the idea of replacing a $200 smartphone than a $1,000-plus all-in-one GPS device, and the idea that the cost of the smartphone was likely to remain stable because of market forces, an added incentive.

There’s another acronym involved here: ROI. Companies are finding even more ways to use the smartphone’s collected data and location-based applications to feed the bottom line.

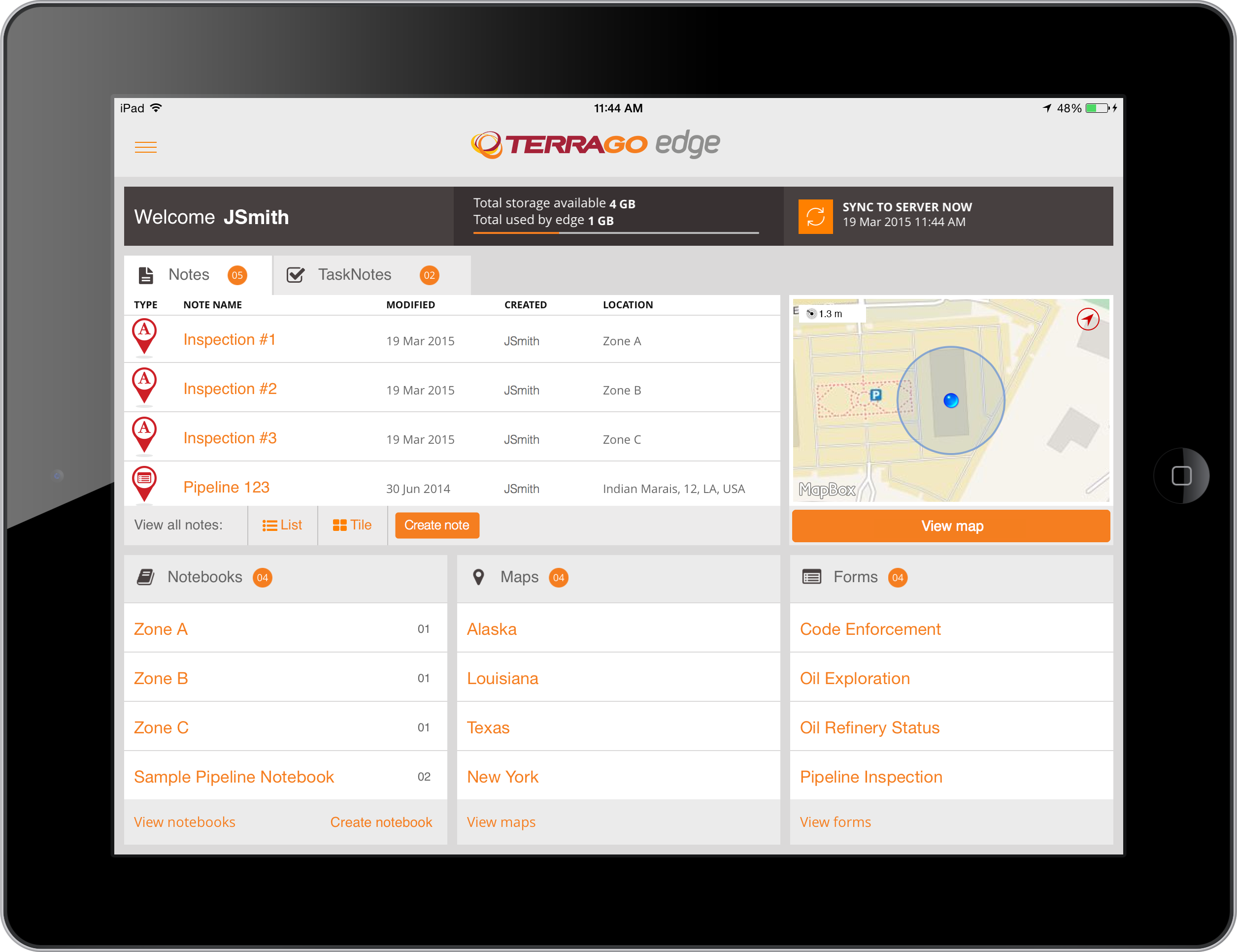

Environmental engineering firms are increasingly replacing paper forms and GPS devices with BYOD apps such as TerraGo Edge.

Environmental engineering firms are increasingly replacing paper forms and GPS devices with BYOD apps such as TerraGo Edge.

It wasn’t long before agile GPS companies understood the phenomenon and spurred it along with their own innovations.

Companies such as TerraGo, with its Edge, and GoSpotCheck and others created applications to foster mobile data collection and collaboration with the smartphone.

While one of the great ironies with the smartphone is its refusal to improve voice modulation to enhance phone calls, its capabilities to foster communications improve steadily with the help of data-sharing applications. Where once data-sharing was a one-way street, from the field to headquarters, now communications flow in both directions, with the field annotating maps, then getting results back from the home office in quick time. The growing concept of democratization of data is fed by this dynamic, and both ends of the continuum benefit from it.

The data flow is enhanced by the smartphone’s picture-taking capability. When 22-megapixel pictures and video are joined with automatically created forms and other creations in the data package, the report becomes richer and more meaningful.

Add to that the ability to work offline—the chief selling technique GPS manufacturers used for a while was pointing to a horizon without cellphone towers—further enhances the smartphone’s capability. Field crews simply learned to preload maps, do their work offline in remote areas, and then send the data back when connectivity was available. Problem solved.

A Canadian pipeline surveyor recently made the switch from an all-in-one device to one that used a smartphone app and Bluetooth GPS receiver after learning that 1) the results it got were as good or better than the all-in-one device; 2) the cost of equipment per unit was less than $10,000, a $60,000 savings; and 3) the cost of labor in data collection dropped 75 percent because the workflow eliminated duplicative steps by benefitting from real-time data processing.

With employees already carrying smartphones, more companies are leaving GPS handsets behind.

With employees already carrying smartphones, more companies are leaving GPS handsets behind.

The bad news the all-in-one GPS providers are seeing now will continue, especially with smartphone manufacturers adding the Russian GLONASS, European Galileo, Chinese Beidou and other location satellite systems to their portfolio.

Those same manufacturers are paying attention to Moore’s Law, offering better GPS chips, cloud data storage and faster data retrieval with each iteration of their products.

So, too, are commercial app developers using agile development methods to rapidly enhance its applications that provide increased capability to smartphone and tablet users with over-the-air updates. When you learn that TerraGo Edge has delivered nine product releases to customers in its first year, you understand that the old ways of developing GPS software and traditional handsets are being left far behind.

That wave is being fed with the rushing trend toward the Internet of Things, in which smartphones deliver a variety of sensors and information. Along with its GPS capability, the device is being increasingly considered an independent, mobile operating system, as opposed to its single-purpose predecessor.

New capabilities of the smartphone and tablet computer are revealed with each iteration, and many of those capabilities are still in their nascent stages. The devices are riding a wave that industry is surfing, a wave that’s crashing down on the all-in-one GPS device.

Jim Hodges, Geospatial Technology Analyst and Journalist; e-mail: jimhodgeswrite at gmail.com.