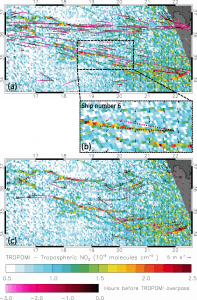

Nitrogen dioxide concentration patterns under sun glint conditions. (Credit: Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2018), processed by Georgoulias et al.)

Maritime transport has a direct impact on air quality in many coastal cities. Commercial ships and vessels burn fuel for energy and emit several types of air pollution as a byproduct, causing the degradation of air quality. A past study estimated that shipping emissions are globally responsible for around 400,000 premature deaths from lung cancer and cardiovascular disease, and 14 million childhood asthma cases each year.

For this reason, during the past decade, efforts to develop international shipping emission regulations have been underway. Since January 2020, the maximum sulphur dioxide content of ship fuels was globally reduced to 0.5% (down from 3.5%) in an effort to reduce air pollution and protect health and the environment. It’s expected that the nitrogen dioxide emissions from shipping will also become restricted during the coming years.

Monitoring ships to comply with these regulations is still an unresolved issue. The open ocean covers vast areas, with limited or no capacity to perform local checks. This is where satellites, such as the Copernicus Sentinel-5P satellite, come in handy.

Until recently, satellite measurements needed to be aggregated and averaged over months or even years to discover shipping lanes, limiting the use of satellite data for regulation control and enforcement. Only the combined effect of all ships could be seen, and only along the busiest shipping lanes.

In a recent paper, an international team of scientists from the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI), Wageningen University, the Human Environment and Transport Inspectorate of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, and the Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, have now discovered patterns in previously unused “sun glint” satellite data over the ocean that strongly resemble ship emission plumes.