“Is my property being taxed fairly?”

“Is my property being taxed fairly?”

“Are zoning variances being granted in a consistent manner?”

“Is my flood insurance rate justified?”

These are the types of questions concerned citizens may ask, both in their own interest, and in the interest of maintaining a responsive and equitable democracy. Our democratic system of government is supposed to conduct the public’s business fairly and consistently within the explicit directives of the citizens’ elected representatives. But how can citizens know if that is happening? And how can citizens know that their representatives are actually conducting “the people’s business” rather than their own? Transparency is required for maintaining our governments’ accountability to its citizens.

Transparency means giving citizens access to their governments’ records, to the same information that government agencies themselves use to make decisions and conduct operations. With it, interested persons can understand, verify, and possibly challenge a governmental action. Since most governmental actions impact specific locations, geographic information is critical to governmental accountability, and GIS technology and professionals are critical to analyzing that information.

Perhaps the three most important types of geographic data necessary to locate the object of a particular government action are the parcel basemap, street centerlines, and addresses associated with parcels. Of the 3,140 counties in the United States, approximately 70% have converted their maps to digital geographic data.

The conversion process was expensive, and the costs of maintaining and updating digital land records are also significant to most governmental agencies. But most agencies recognize that the value of using digital basemaps to conduct official duties exceeds the initial and ongoing investment. However, some agencies, approximately 30% of the counties, believe that they have to charge a fee for the use of their GIS basemaps in order to defray the costs. Fees that are greater than the direct costs of duplicating these government records are an impediment to citizens’ access to the data, and therefore become a threat to governmental transparency and accountability.

The situation is similar in California, where until recently, 11 of California’s 58 counties sold their parcel basemap data at more than the cost of duplication, in violation of California’s Public Record Act (now the number is 8). Like the Freedom Of Information Act (FOIA) that mandates public access to our Federal government’s data, each state has its own Public Records Act (PRA) that mandates public access to state and local governmental data. While each state’s PRA is a bit different, recent lawsuits in California provide useful lessons for all citizens, and for all GIS professionals.

In the early 2000s, over 30 of California’s counties required requesters to pay thousands of dollars, or more, for a copy of their digital parcel basemap. How could this happen when California’s PRA clearly states that public agencies can charge no more than the direct cost of duplication? [California Govt. Code §§6250-6270, specifically here, §6253(b). Herein, “PRA” means Public Records Act and CPRA refers specifically to California’s PRA.] Well, nobody had ever challenged those policies. Utility companies and a few municipalities that could afford to pay the price obtained these public records, while everyone else went without.

Some cities decided it was more cost effective to develop their own digital basemap, resulting in taxpayers paying for multiple digital map creation in both their city and their county. When the state Emergency Services GIS team arrived in Los Angeles to assist after the Northridge earthquake (in 1994), L.A. County insisted that they pay $22,000 for the part of the digital basemap covering the affected area. That fee was subsequently waived, after much negotiation, and the GIS team was able to map the damage and help plan for the recovery. But, in 2003 two GIS professionals, this author and Dennis Klein, decided that the CPRA had to be affirmed.

A written request was made to Santa Clara County, CA, for its digital basemap data, and the answer, received within 10 days as prescribed by the CPRA, was that the data could be obtained only after signing a restrictive licensing agreement and after paying the fee of $158,000. When questioned that its policy violated the CPRA, the County representative said that “no determination had been made.” So, we filed an official complaint to the state Attorney General to determine whether a county’s parcel boundary map in digital format was covered by the CPRA.

The Attorney General’s office took a year to consider the question; it surveyed the state’s county assessors and received letters with opinions from GIS professionals and companies that use parcel basemaps in their business. In October, 2005, the AG’s office issued an official opinion [88 Ops.Cal. Atty.Gen 153 (2005)] affirming that digital parcel basemap data was subject to the inspection and copying provisions of the CPRA, including the fee limitations. Subsequently, over the next few years, 20 California counties changed their data access policies to conform with the CPRA. But a few counties held out. Their Assessors said that the Attorney General’s Opinion was just an opinion, it is not a legally binding determination which requires a judicial decision through a court of law. One Assessor said (privately and off the record), “if you want our data (according the CPRA conditions), you’ll have to sue us.”

The California First Amendment Coalition (FAC) is a non-profit organization that fights to protect news reporters’ rights and freedoms, including their access to government records [Since the court case, California First Amendment Coalition (CFAC) changed its name to First Amendment Coalition (FAC).]. FAC’s members are newspaper publishers and citizens who believe in keeping good government good by keeping it transparent. They were responsive when this author approached them for legal assistance in obtaining Santa Clara’s digital basemap under the CPRA, in part because many of their newspaper members were beginning to use GIS for investigative reporting.

In subsequent Amicus letters, the Embarcadero Publishing Company stated that a GIS basemap linked to demographic data and environmental hazards would permit comprehensive reporting on risk exposure by different socio-economic groups in the County. The San Jose Mercury News affirmed that access to the County’s digital basemap would enable its reporters to systematically assess whether poor neighborhoods were being shortchanged for road repairs, and by comparing the tax treatment of hundreds of similar residential properties, they could draw conclusions about the fairness of property tax assessments.

GIS comparison of street paving condition with neighborhood income convinced the Petaluma city council to redeploy Public Works department resources.

GIS comparison of street paving condition with neighborhood income convinced the Petaluma city council to redeploy Public Works department resources.

In June, 2006, FAC sent a letter of demand to Santa Clara County for its basemap data under CPRA provisions, and received a prompt refusal within 10 days. It filed a petition with the Superior Court to enforce the CPRA in October, 2006. A lawsuit was launched.

The County argued that the Attorney General’s Opinion did not apply to its “sophisticated GIS basemap,” that its basemap data was protected by copyright, and that its basemap data was exempted by state law as software. In sworn statements, County GIS and IS managers asserted, “… ‘applications software’ is understood to include the instructions that manipulate data and the databases on which those instructions operate.” The Court didn’t buy those arguments and, in May, 2007, ordered the County to provide its data to FAC as required by the CPRA. The County appealed in June, 2007, just after it had its data designated as “Protected Critical Infrastructure Information (PCII) by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

The Critical Infrastructure Information Act of 2002 is part of the Homeland Security Act [6 U.S.Code §131-134] that enables utility companies to send their technical and map data to the DHS so it can create disaster (and terrorism) preparedness plans. When such data is designated as PCII, other agencies, including potential competitors of the utility company, can not access this information through a Federal FOIA request. Santa Clara County was asserting that its parcel basemap contained “Protected Critical Infrastructure Information” even though only parcel boundaries were present, and further, that the PCII designation exempted it from PRA requests.

As the Court of Appeal deliberated, several interested third parties sent the Court “friend of the court” (Amicus) briefs to elucidate such technical issues as the difference between “critical infrastructure” and parcel boundaries, the difference between software and data, the purpose and function of the Homeland Security Act, and the applicability of copyright protection to government data. Among the briefs, one was co-signed by 55 GIS Professionals and 22 geospatial organizations.

The Court of Appeal decided in February, 2009 that the County must provide its parcel basemap data to FAC according to CPRA regulations. The Court affirmed that DHS regulations make a distinction between submitters of critical infrastructure information (to DHS) and recipients of PCII (from DHS). The federal prohibition on disclosure of PCII applies only to requesters of PCII from DHS. In other words, DHS can not redistribute PCII data under FOIA regulations, but the originator and creator of that data is still subject to its state’s Public Records Act. PCII designation does not shield a County from its PRA obligations. The Court noted that this designation was sought only after FAC filed suit, and irrespective of the County’s past sales of the GIS basemap to 15 purchasers, some of them private entities.

Further, the Court affirmed that there is no statutory basis either for copyrighting the GIS basemap or for conditioning its release on a licensing agreement. Individual state laws determine whether public agencies within their jurisdiction can copyright the data they create in the course of their duties. Many states, including California and Florida, require their legislatures to specifically authorize the copyright privilege for a specific type of data, otherwise, the default is that copyright is not allowed to restrict disclosure or impose limitations on the use of government data.

In its summary, the Court of Appeal said, “We conclude that the public interest in disclosure outweighs the public interest in nondisclosure.” FAC’s executive director, Peter Scheer, noted, “We have always believed that the public should have essentially free, unrestricted access to digital mapping data that were created by the government with public funds. Not only does the public own the basemap, but the public interest will be served by making it available to companies, individuals, nonprofits, journalists — and even to other government agencies.”

The case still wasn’t over. The County tried to get the decision “depublished” so it couldn’t be used to set precedent. The Court rejected that request. Then, the County tried to fulfill the Court order with a three-year-old copy of the geodatabase (dating back to the date of the initial lawsuit), then with the previous year’s version. We insisted on the then-current version (Q3, 2009), in both .shp and .gdb format, which they eventually acceded to in September, 2009. Nevertheless, we had to request the 2008 annual version as well, because the 2009 version did not include the text annotation that is present in the 2008 version. Santa Clara County had been selling its geodata for $158,000; the cost FAC finally paid was $3.10, plus shipping.

[CFAC’s attorney was Ms. Rachel Matteo-Boehm, rachel.matteo-boehm [at] bryancave.com]

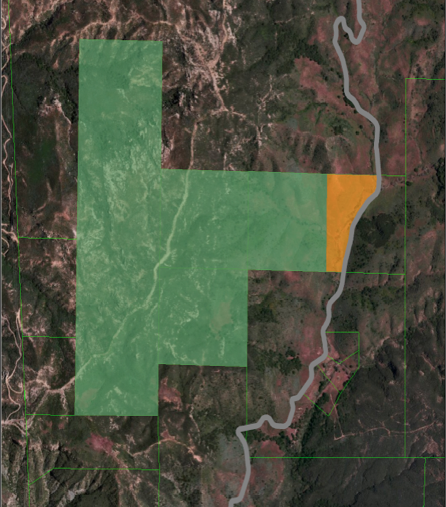

Two years before the Santa Clara decision, in June, 2007, the Sierra Club made a CPRA request to Orange County, CA, for their digital parcel basemap. They wanted to maximize the impact of purchasing the development rights of selected parcels for the creation of a nature preservation zone. They needed to analyze the entire landbase, along with environmental and other layers, to make their purchase selection. In July, 2007, they received the County’s refusal to give them the digital basemap for the cost of duplication, citing its copyright. The County was selling its landbase for $475,000, and offered the Sierra Club a “deal” of $75,000 a year for five years.

Geoanalysis identifies opportunities to leverage purchase of development rights to maximize habitat preservation.

Geoanalysis identifies opportunities to leverage purchase of development rights to maximize habitat preservation.

A year later, Sierra Club requested again, and was refused again. This time, the County cited the “software exclusion” of the CPRA, but offered “responsive records” in the form of paper copies (or .pdf files) of all the source maps used to compile their digital landbase. Nine months later, March 2009, after the Santa Clara decision was issued, Sierra Club made another CPRA request, which again was refused. So, in April, 2009, they filed a CPRA lawsuit (“Petition for Writ of Mandate to Enforce Public Records Act”) against Orange County, saying: Unless Sierra Club obtains the requested public records, the public will be denied information prepared at public expense pertaining to the conduct of the public’s business essential to monitor its government.

Orange County’s “software defense” was more sophisticated than Santa Clara’s was. Their more experienced lawyers sought to exploit an ambiguous section of the CPRA, section 6254.9, the “software exclusion.” The law reads, in part:

“(a) Computer software developed by a state or local agency is not itself a public record under this chapter. …” and

“(b) As used in this section, “computer software” includes computer mapping systems, computer programs, and computer graphics systems.”

The Legislature never defined “computer mapping system” (CMS) and this gave Orange County’s lawyers a loophole. They argued that a CMS is like a GIS. Then they cited the definition of “GIS” from ESRI’s “GIS From A to Z” (2006):

“GIS is an integrated collection of computer software and data (emphasis added) used to view and manage information about geographic places, analyze spatial relationships, and model spatial processes.”

The County’s logic was:

Sierra Club’s lawyers and its GIS expert (the author) argued that the “System” in “Geographic Information System” refers to all the elements necessary to make GIS technology useful, including: hardware, software, data, application programming, data models, staffing & training, administration & management, maintenance procedures & standards, even financing. Without all of these, your GIS will hardly perform. In 1988, when “computer mapping systems” was put into §6254.9(b), “system” referred to software modules (input, processing, output, etc.). Oh, if GIS professionals knew in 2006 how the definition would be mis-interpreted, we might have said, “GIS is a collection of computer software used to integrate data to view and manage information …”

The legal word games extended to the meaning of “includes” in §6254.9(b). Sierra Club said “includes” means “computer mapping systems, computer programs, and computer graphics systems” are examples of software. The County said “includes” means “computer mapping systems” is an enlargement of the definition of software to include data.

While words like “software,” “data,” “computer mapping,” “system,” “database,” and “GIS” are clear to GIS professionals. To lawyers, judges, and people not steeped in our technology, these terms could mean just about anything. The opposing experts’ testimony didn’t lead to resolution. The Superior Court decided in favor of Orange County in April, 2010 [In August, 2010, the Court issued its “final statement of decision.”]. The Judge agreed that the “software exemption” did include GIS data, and he believed that the underlying information (in paper or .pdf format) would fully satisfy the CPRA’s intent of providing government information to its citizens. He said,

“Section 6254.9 creates an exemption for GIS file formatted data, but it nevertheless guarantees the public access to non-GIS formatted records containing information stored in a GIS …”

During the hearings, the Judge asked, “When someone requests information, is it just the data that is required, or is it also the data format, which enables manipulation?” Does ‘information’ include its data structure in the database? GIS professionals know how GIS can analyze a database far better than a human can analyze paper maps; the answer is obvious, but to outsiders, this was a serious ponder.

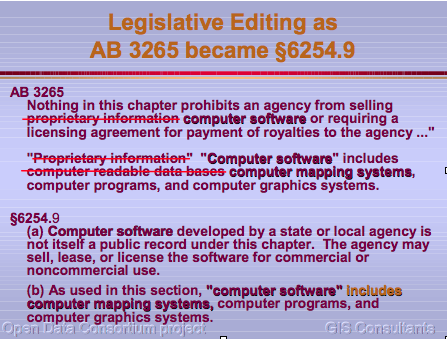

Justice requires persistence, and Sierra Club appealed the case in August, 2010. When a court decides on ambiguous terms, like “computer mapping system,” it refers to the “legislative intent” at the time the law was passed. Sierra Club acknowledged that when the original bill, AB3265, was introduced by the City of San Jose, its intent was indeed to recoup the considerable cost of building its AM/FM system database. The text which later became §6254.9 originally said:

“Nothing in this chapter prohibits an agency from selling proprietary information or requiring a licensing agreement for payment of royalties to the agency …,” and ” ‘Proprietary information’ includes computer readable data bases, computer programs, and computer graphics systems.”

Sensitive to the problem that this would severely limit the public’s access to government data, the state Assembly changed the term “proprietary information” to “computer software” and the state Senate replaced the term “computer readable data bases” with “computer mapping systems.” [Fig. 7] Sierra Club argued that this proved the legislative intent was not to exclude GIS or CMS database data from CPRA access requirements.

Orange County countered by digging deeper into the legislative history, citing the state Finance Department’s fiscal analysis of the original AB3265 bill, which stated, “The potential revenue generated by the sale of computer programs, graphics, and information data bases could be substantial …” After the term “proprietary information” was replaced with “computer software” and “computer readable data bases” was replaced with “computer mapping systems,” the report remained unchanged. Was that because the Finance Department never got around to revising its report after the Legislature’s changes? The County argued that this indicated that the intent of the “software” exclusion was to exempt computer mapping system databases so they could be sold to recoup the agency’s investment.

The County stated that its GIS landbase cost millions to develop and that revenue from its sales covered 26% of operation and maintenance costs. It argued, “Petitioner is asking the Court to compel County taxpayers to subsidize Petitioner’s enjoyment of the functionality of a GIS without contributing to the costs of maintaining such a system.” But, in fact, the County was charging its own taxpayers, including the Orange County Fire District, for the data they had already paid for. The County even charged its own departments (Registrar of Voters).

In May, 2011, the Court of Appeal sided with Orange County. The Court said that it saw its role as discerning the intent of the Legislature in passing a poorly defined law, not as the arbiter of good or poor public policy. Its decision concluded, “whether the increasing use of GIS data in our society requires reconsideration of section 6254.9’s exclusion from disclosure is a matter of public policy for the Legislature to consider.”

Persistence requires patience, and Sierra Club appealed to the California Supreme Court in July, 2011. Many petitioners seek Supreme Court judgment, only 3% of those cases get heard. First, the Court decides if it will take the case. Five “friends of the Court” filed Amicus letters urging the Court to take the case, including one from the “GIS Community” co-signed by 11 GIS organizations and 72 GIS Professionals. In September, 2011, the Supreme Court agreed to hear this case.

While clarifying the legal, procedural, and historical arguments, Sierra Club kept the principle foremost. At stake was whether the public has unfettered access to the GIS-compatible data that its government agencies use to conduct “the public’s business,” in the same geodatabase format that the agencies themselves use, or whether the government can license, restrict and charge high prices for such access. As more and more governmental decisions and actions are based on GIS analysis, the issue is central to governmental transparency and accountability to us, the citizens of our democracy.

Seven groups submitted Amicus briefs in support of Sierra Club, including one from the GIS Community now co-signed by 212 individual GIS Professionals and 23 GIS organizations. Once more, they explained that “computer mapping systems” refers only to software, not to the data on which the software operates. Further, they explained that .pdf files are not equivalent to a GIS-compatible database, and that the public’s right to inspect and review the exact same data that Orange County uses to make its decisions would be curtailed by .pdf-only data. They explained how upholding Orange County’s ability to sell government geodata countered the trend toward open data nationally, and Federal geospatial data policies specifically. Three groups, the League of California Cities, the California State Association of Counties, and the California Assessors Association, wrote Amicus briefs for Orange County [One may wonder why these organizations backed Orange County when a majority of their member agencies have open data distribution policies].

It took a year and 10 months for the California Supreme Court issued its unanimous decision, in July, 2013, starting with:

“Openness in government is essential to the functioning of a democracy. Implicit in the democratic process is the notion that government should be accountable for its actions. In order to verify accountability, individuals must have access to government files.”

The Justices went on to clarify any remaining doubt about the proper interpretation of §6254.9 by citing Article I, Section 3, Subdivision (b)(2), of the California Constitution:

“A statute, court rule, or other authority … shall be broadly construed if it furthers the people’s right of access, and narrowly construed if it limits the right of access.”

and

“To the extent that the term ‘computer mapping system’ is ambiguous, the constitutional canon requires us to interpret it in a way that maximizes the public’s access to information, unless the Legislature has expressly provided to the contrary.”

and

“It seems implausible that the Legislature, having expressly stated that ‘information . . . stored in a computer is a type of public record subject to disclosure’ (§6254.9(d)), and having provided for access to such information ‘in any electronic format in which [the agency] holds the information’ (§6253.9(a)(1)), would have intended to exclude large categories of computer databases (mapping and graphics) merely because the files they contain are formatted to be read and manipulated by mapping and graphics software.”

Shortly thereafter, Orange County posted its GIS landbase on the web for free download. Determination to assert one’s rights fueled the Sierra Club’s persistence and patience through 51 months, since filing the lawsuit. 73 months had elapsed since making the initial PRA request for the County’s basemap.

[Sierra Club’s attorney was Ms. Sabrina Venskus, venskus [at] lawsv.com]

Since 2004, GIS professionals and good government activists have been fighting to apply California’s Public Record Act to gain access to governmental GIS basemaps. Part 1 of this story described two significant lawsuits that finally enable citizens to access government geodata free of excessive fees or license restrictions. This data gives GIS professionals the ability to analyze our governments’ decisions and hold them accountable. In Part 2, we review lessons learned from this ordeal.

The questions from the Justices during trial hearings and their written decision, indicate that the explanations proffered in the GIS Professionals’ Amicus brief informed the Court. They better understood both the technical nature of geodatabases as well as the implications of their decision on the GIS community and the people GIS professionals serve, as well as on the entire society. GIS professionals’ special gift is an understanding of geospatial technology and of the analyses it can perform in nearly every discipline of professional service. Therefore, it is our responsibility to attend to policies, good or bad, that are derived through using GIS, or that would restrict the use of GIS. We must look beyond our colorful computer screens and engage in the political world, the legal world, the economic world, as well as the more familiar environmental, engineering, and planning domains.

Working with many individuals and professional organizations to gain their participation and consensus on the Amicus briefs reminded me about active listening, about finding common principles for agreement, and about standing up for those principles even when it disrupts the comfort of status quo. If we don’t arise to challenge what ain’t right, we perpetuate what is wrong.

Standing up for the public good may be altruistic, but it does not preclude “doing well by doing good.” There are opportunities here for GIS professionals to open community consultancy services to help people determine whether their property is being appraised fairly for tax purposes, or whether building permits or zoning variances are being issued equitably, according to standard criteria.

PRA requests must be very specific, or you might not get what you thought you asked for. Asking for “parcel basemap in electronic format” may return a .pdf file instead of a geodatabase or .shp files that can be imported into your GIS. It is recommended to ask for “GIS parcel basemap polygons, georeferenced and tagged with APN” to avoid being given a CAD file of unclosed polygons. Also, ask for situs address, owner’s name and address, and street centerlines with street name annotation.

How will you know whether the geodata you receive is current and accurate? PRA requests should ask for the files’ metadata, including the date of data capture, date the data was extracted from the geodatabase, and the basemap’s projection, datum, epoch, state plane coordinate zone, and locational accuracy (or error tolerance).

How will you know what some of the database descriptive attributes refer to, or how the database tables relate to each other? PRA requests should include the database dictionary, schema or E-R diagram, and descriptive documentation for users and system managers.

While some states’ PRAs allow local governments to copyright the data they create and others do not, one should remember the purpose for copyright. Article I, Section 8, Subsection 8 of the U.S. Constitution states:

“The Congress shall have the power to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”

This suggests that there are creations that need the incentive of exclusive control by the creator before the creative act will occur. Government agencies operate by mandate; they don’t need commercial incentives to perform their duties [this argument was sagely put forth by Professor Earl Epstein of The Ohio State University]. Further, copyright protection would annul a PRA. Virtually any type of original work of authorship prepared by an employee of a public agency, including letters, emails, memos, reports, charts, photographs, graphic drawings, etc., could qualify for copyright protection. Citizens would be shut out from their governments’ records and data files.

So what happens when a public agency buys data, say aerial photography or LIDAR data, from a private company, and uses it to formulate its decisions and activities in conduct of “the people’s business?” The public agency may have signed a non-disclosure licensing agreement; the data belongs to the private company that created it; but, the public still has a right to see the information its governmental agencies use to do their governing. In 2009, California’s then-CIO, Terri Takai, issued a clarifying memo:

In other words, a person can obtain the copyrighted data that a public agency uses, but he/she is still subject to the data owner’s copyright: he/she can view it and analyze it, but can not distribute nor sell it without getting permission from the copyright holder.

In this era of the ever-tighter squeezing of governmental budgets, two important principles conflict with each other. One, the necessity of citizens to access their governments’ data in order to know what they are doing, conflicts with Another, government’s need to find the revenues to pay for expensive geodatabase creation and ongoing maintenance. Some agencies hope to pay for their geodata by selling it.

There are many ways that a government agency can mitigate the considerable cost of creating and maintaining its GIS basemap. Primarily, the return on this investment comes from the greater efficiency and better decision-making that GIS data provides to government operations. Less time and effort is needed to perform jobs such as notifying property owners within 1,000 feet of a proposed zoning variance. Street-sweeping routes can be optimized, thereby removing the need to purchase another expensive, street-sweeping machine. The benefits from using GIS data save our governments money. And the more people who use an agency’s geodata, the more benefits accrue.

Unfortunately, at this time, the benefits and savings are not well tabulated in a systematic manner. The money saved by not purchasing a street-sweeping machine may be used for additional pot-hole repair instead, so the Return On Investment (ROI) from the GIS department that maintains this data is not easily accounted for. If it were, there would be no need for a government agency to sell its data in order to support its GIS operation.

The National States Geographic Information Council (NSGIC) issued an informative brochure extolling the benefits of open access to public agency geodata, and debunking the myths that have supported governmental sale of that data [See http://nsgic.org/public_resources/NSGIC_Data_Sharing_Guidelines_120211_Final.pdf]. NSGIC recommends that governments review their data distribution policies and adjust them, if necessary, to provide their data more openly and accessibly. Recently, NSGIC published a guide for public agencies to calculate the ROI of their geospatial operations [See http://www.nsgic.org/roi_cba_review]. A small percentage of the tabulated net benefit could be allocated to funding an agency’s ongoing GIS operations.

One hard-boiled defender of governmental data sales complained it wasn’t right that some garage-based entrepreneur could get his agency’s data for free and then sell it as tourist maps and make a fortune. He hadn’t realized that, wherever potential tourists may be located, when they use the map to guide their vacation, they would be spending money in his government’s jurisdiction. More geodata users create more economic activity which results in more tax revenue for the public agency.

In 2004, the Federal Geographic Data Committee commissioned the Rand Corporation to suggest what kind of governmental geodata might pose a potential security threat severe enough to remove it from public domain. Three criteria were recommended before deciding to remove information from the public record because of potential security concerns: the usefulness of the data to terrorists, the uniqueness of the data, and a comparison of the societal benefits vs. the costs of restricting the data from general public use [Cf. John C. Baker et al. “Mapping the Risks: Assessing the Homeland Security Implications of Publicly Available Geospatial Information.” Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, 2004, p. 126]. In the case of Santa Clara County’s attempt to withhold its parcel basemap as Protected Critical Infrastructure Information:

(1) The data did not show/describe information about critical potential targets (critical infrastructure), nor did it provide sufficient specificity to significantly aid a potential attack (accurate location of critical “choke points”).

(2) The information was available elsewhere in the public domain (Google Earth, and local city basemaps); the County’s basemap was not a unique source of that information.

(3) The loss to the public from withholding the data was far greater than the slight risk of possible damage that could be caused by its availability.

Some movie stars have objected to their names being linked to the land parcels they own in public records, as a threat to their privacy. But the identity of property ownership is absolutely necessary if one were to investigate apparent aberrations from a uniformly applied tax assessment. If an official was illegally under-assessing his friends (not necessarily movie stars), property ownership information would be critical to exposing the corruption. The security of keeping our governments honest and accountable depends upon public access to property ownership information.

There are many kinds of data, however, that rightfully are withheld to protect individual privacy. PRA laws list them explicitly, for example:

Geographic data is not listed as exempt from public record disclosure.

Some PRAs prohibit a state or local agency from anonymously posting the home address or telephone number of any elected or appointed officials, or law enforcement officers, on the Internet. The owner names linked to parcels in GIS basemaps do not identify the occupation nor official capacity of the owner. Nevertheless, prudence recommends that PRA requesters identify themselves before being given access to download basemap data from the Internet. Public agencies can not restrict access according to who requests the data, nor can they even ask what the requester’s purpose is for using the data; a requester does not have to justify or explain the reason for exercising a fundamental right. But agencies can keep tract of whom they have given their data to.

In 1988, when the Legislature was confronted with two opposing interest groups (cities like San Jose that wanted permission to sell their geodata on one hand, and advocates for public access to government data on the other), they finessed a solution by creating a law with ambiguous terminology (“computer mapping system”). Everyone thought their position had prevailed! Such is the art of politics. This could be a cautionary tale, because years and effort were subsequently spent trying to resolve the ambiguity of the law’s intent. It could also be instructive in the art of compromise: don’t push for clarity that might upset the agreement. If GIS professionals aspire to have a law enacted or changed, they should be well aware that the result may not look like what was intended. And the language may not even mean what it looks like it means!

Concerned citizens need to be alert, constantly, for legislative attempts to roll back our freedom to oversee our governments. In recent months, the California Legislature passed the annual state budget – on time for the first time in a decade. As the bill was being rushed to the Governor’s desk for signing, an alert watchdog noticed that an obscure provision would have made the Public Records Act optional. That’s right, agencies would have had the option of selling their data or withholding it entirely! Fortunately, some newspapers exposed this landmine, and many citizens, along with the First Amendment Coalition and a few GIS professionals, immediately contacted their representatives demanding the bomb be removed. Fortunately, it was. Concerned citizens sometimes need to act quickly [We discovered later that the lobbyist working for a Southern California county which had recently lost a lawsuit was trying, a bit too single-mindedly, to sneak this last-minute language into the budget].

A lot of attorney time was expended in each of these PRA lawsuits. How can the average citizen or non-profit organization afford to enforce their legal rights? Preservation of the public’s access to its government’s documents is so important, that California’s PRA makes the government agency pay the court costs and the plaintiff’s attorney’s fees if the plaintiff prevails. If the public agency prevails, the plaintiff does not have to pay the agency’s attorney fees, unless the lawsuit is determined to be “clearly frivolous.” Santa Clara County’s, and Orange County’s, taxpayers were not so lucky. They ended up footing the bill for their governments’ misguided data sales policies.

This is not the first time, nor will it be the last time, in which the GIS community is called upon to lend its expertise and participation, to defend and extend our democratic rights and our professional integrity. Liberty requires vigilance. Working together, our efforts can make a difference.