Frequently in the news, Earth’s declining ice is without doubt one of the biggest casualties of climate change. However, calculating the amount of ice we are losing can be a challenge.

Frequently in the news, Earth’s declining ice is without doubt one of the biggest casualties of climate change. However, calculating the amount of ice we are losing can be a challenge.

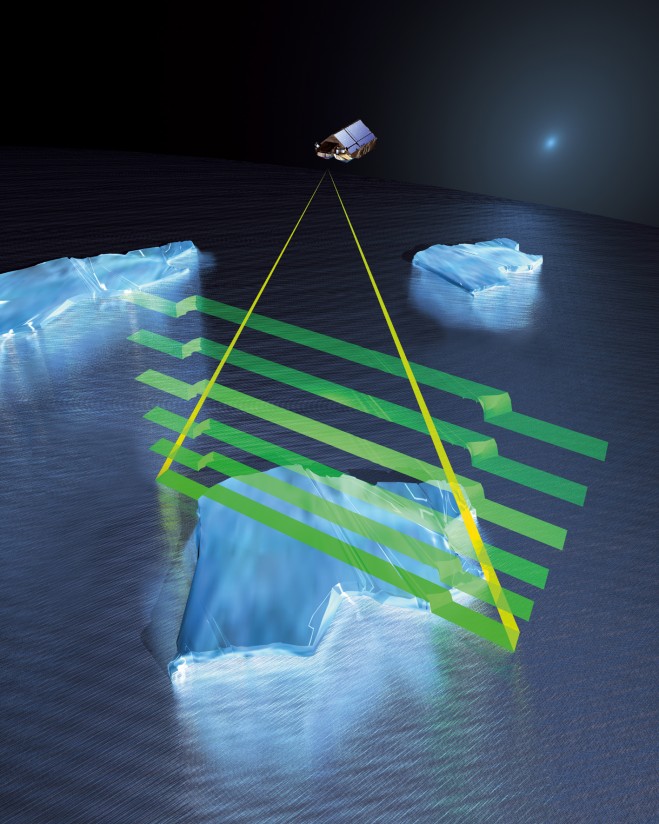

While monitoring the area of land and ocean covered by ice is relatively straightforward using images from satellites carrying camera-like instruments, scientists need to understand how the actual volume is changing—and to calculate this, they need measurements of ice thickness.

ESA’s CryoSat altimeter returns readings of ice height by timing how long it takes for radar waves to bounce back to the satellite from the ice surface. When it comes to ice floating in the polar oceans, ice thickness is inferred by measuring the height of the ice above the water.

However, these measurements can be distorted by the weight of overlying snow pushing it down into the ocean water. Scientists adjust for this effect using a map of average snow depth based on historical field measurements, but this map is now out of date and does not account for the impact of climate change on Arctic snowfall and regional snow-depth variations.

A paper published recently in The Cryosphere describes how researchers swapped the old map of snow depth for the results of a new computer model that calculates snow depth and density using inputs such as air temperature, snowfall and ice motion to track how much snow accumulates on sea ice as it moves around the Arctic Ocean.

By combining the results of the snow model with radar observations from CryoSat and Envisat, they estimated the overall rate of decline of sea-ice thickness in the Arctic as well as the variability of sea-ice thickness from year to year.

They concluded that sea ice in key Arctic coastal regions is thinning at a rate of 70-100% faster than previously thought. In particular, they found that in the coastal regions of Laptev, Kara and Chukchi seas, the rate at which ice is thinning increased by 70%, 98% and 110% respectively, when compared to earlier calculations.

Image Credit: ESA /AOES Medialab

There are no upcoming events.