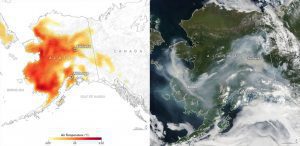

In June and early July 2019, a heat wave in Alaska broke temperature records, as seen in this July 8 air temperature map (left). The corresponding image from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument on Aqua on the right shows smoke from lightening-triggered wildfires. (Credit: NASA Earth Observatory)

Hot and dry. These are the watchwords for large fires. While every fire needs a spark to ignite and fuel to burn, it’s the hot and dry conditions in the atmosphere that determine the likelihood of a fire starting, its intensity and the speed at which it spreads. Over the past several decades, as the world has increasingly warmed, so has its potential to burn.

Since 1880, the world has warmed by 1.9 degrees Fahrenheit, with the five warmest years on record occurring in the last five years. Since the 1980s, the wildfire season has lengthened across a quarter of the world’s vegetated surface, and in some places like California, fire has become nearly a year-round risk. 2018 was California’s worst wildfire season on record, on the heels of a devasting 2017 fire season. In 2019, wildfires have already burned 2.5 million acres in Alaska in an extreme fire season driven by high temperatures, which have also led to massive fires in Siberia.

Whether started naturally or by people, fires worldwide and the resulting smoke emissions and burned areas have been observed by NASA satellites from space for two decades. Combined with data collected and analyzed by scientists and forest managers on the ground, researchers at NASA, other U.S. agencies and universities are beginning to draw into focus the interplay between fires, climate and humans.