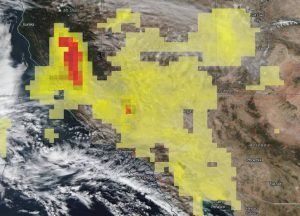

In this image taken Nov. 15, 2018, from NASA’s Suomi NPP satellite, the levels of ozone from the ongoing California fires were mapped using the Ozone Mapping Profiler Suite (OMPS)/National Polar orbiting Partnership (NPP) Total Column Ozone Product 1-Orbit L2 Swath. (Credit: NASA Worldview, Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS))

Although most people might think smoke rises and then clears after a fire has been extinguished, the opposite is actually true. New research using data collected during NASA airborne science campaigns shows how smoke from wildfires worldwide could impact the atmosphere and climate much more than previously thought. The study, led by researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology, found brown carbon particles released into the air from burning trees and other organic matter are much more likely than previously thought to travel to the upper levels of the atmosphere, where they can interfere with rays from the sun—sometimes cooling the air and at other times warming it.

Quoting from the NASA.gov feature: “Researchers found surprising levels of brown carbon in the samples taken from the upper troposphere—about seven miles above Earth’s surface—but much less black carbon. While black carbon can be seen in the dark smoke plumes rising above burning fossil or biomass fuels at high temperature, brown carbon is produced from the incomplete combustion that occurs when grasses, wood or other biological matter smolders, as is typical for wildfires. As particulate matter in the atmosphere, both can interfere with solar radiation by absorbing and scattering the sun’s rays.”

According to other research conducted by NASA in recent years, the increase in brown-and-black-carbon-producing wildfires that rage across the U.S. every year could itself be a symptom of a warming world. A 2015 analysis of 35 years of meteorological data confirmed that fire seasons have become longer. In addition, climate models predict fire seasons will continue to increase in length and strength across the U.S. in the next 30 to 50 years.