Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier has been in the spotlight in recent years, as scientists have undertaken a multi-part international project to study the vast glacier from all angles. The urgency stems from observations and analyses showing that the amount of ice flowing from Thwaites—and contributing to sea-level rise—has doubled in the span of three decades. Scientists think the glacier could undergo even more dramatic changes in the near future.

Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier has been in the spotlight in recent years, as scientists have undertaken a multi-part international project to study the vast glacier from all angles. The urgency stems from observations and analyses showing that the amount of ice flowing from Thwaites—and contributing to sea-level rise—has doubled in the span of three decades. Scientists think the glacier could undergo even more dramatic changes in the near future.

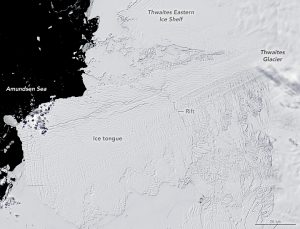

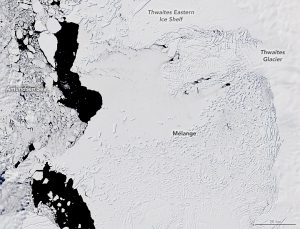

This image pair demonstrates the changes that have occurred since the start of this century. The first image (left), acquired with the Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) on Landsat 7, shows the glacier’s floating ice tongue on Dec. 2, 2001, shortly before it calved iceberg B-22. The second image (right), acquired with the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8, shows the glacier on Dec. 28, 2019.

Both images show the glacier where it exits the land in West Antarctica and stretches over the Amundsen Sea as thick floating ice. Ice that originates on land can raise sea level if it is delivered to the ocean at a faster rate than it is being replaced inland by snowfall. Indeed, Thwaites Glacier is one of the largest contributors to global sea-level rise from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. The flow speed of Thwaites has been increasing, while inland snowfall has not changed significantly.

Notice the size of the glacier’s main ice tongue in 2001, when the glacier was advancing by about 4 kilometers per year. The large rift across the glacier eventually spawned Iceberg B-22 in 2002.

In the last 10 years, the tongue has continued to fracture and separate from the Thwaites Eastern Ice Shelf. By the time the 2019 image was acquired, the main tongue had retreated substantially, and the ocean in front of Thwaites had become filled with mélange, a mixture of icebergs and sea ice.

Image Credit: NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey