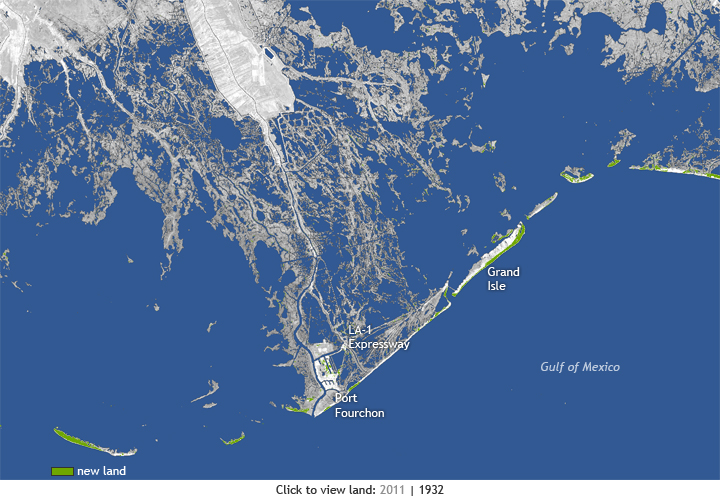

Every year, 25-35 square miles of land off the coast of Louisiana—an area larger than Manhattan–disappears into the water due to a combination of subsidence (soil settling) and global sea level rise. The maps above show how much land has been lost to the Gulf of Mexico in the past 80 years.

The first image shows the state of the coast in 2011. Based on a NASA satellite image, gray and white areas show land and blue indicates open water. New land—mainly coastal improvements such as shoreline revetments and enriched beach areas—that built up since 1932 is shown in green.

How much of what is now open water was once land? The second image shows the state of the coast in 1932. The image combines the 2011 satellite image with a U.S. Geological Survey map in which land areas that were present in 1932 are light gray. Since the 1930s, Louisiana’s coast has lost 1,900 square miles of land, primarily marshes. Toggling back and forth between the two maps reveals the dramatic coastal change.

In Southeast Louisiana, relative sea level is rising at a rate of three feet every one hundred years, according to sixty years of tidal gauge records. Relative sea level refers to the change in sea level compared to the elevation of the land, which can be due to a combination of global sea level rise and subsidence—the settling and sinking of soil over time.

Storm surge—the water from the ocean that is pushed toward the shore by the force of storm winds—takes advantage of the problems caused by subsidence and global sea level rise. Because much of the Louisiana coast is very low in elevation and gradually converting to open water, entire neighborhoods, roads, and other structures are vulnerable to even small storm events.

At the very tip of the coast lies Port Fourchon—one of the country’s major ports serving the deepwater oil and gas industry in the Gulf of Mexico. Next to it is Grand Isle, the last inhabited barrier island in Louisiana. Various beach restoration projects over the years have helped build up and maintain Grand Isle and other Louisiana’s barrier islands. They are the first line of defense against storms headed toward the mainland and New Orleans.

The Louisiana Highway 1 is the only road leading to Port Fourchon and Grand Isle. While the port sits on a five-foot ridge, much of the LA-1 highway is built on land only two feet in elevation. The highway is growing increasingly vulnerable to sea level rise, subsidence, and storm surge every year. One section of the road is so low that even small storm events cause flooding that makes it impassable. Disruptions to the infrastructure surrounding the port have the potential to impact every American at the gas pump.

Sea level rise in Louisiana is a challenge today, not just one for the future, and a wide group of people and organizations are helping develop solutions. Want to know more? Our recent feature story, “Thriving on a Sinking Landscape,” provides an in-depth look at what is at stake for locals and the rest of the country if the LA-1, ‘America’s longest Main Street,’ fails to stay above water.

Satellite data and map layers courtesy of the US Geological Survey. Map by NOAA Climate.gov team. Science reviewer: Stephen Gill.

Source: NOAA